We Play It For The Music | Jet Grind Radio

February 19, 2021

The 1990s and its monolithic legacy is something of an inescapable omnipresence in pop culture. Hip hop was seemingly on every corner, creating a collage of unique rhythms and thought throughout a fluorescent grid of lamps and headlights. By night, the city receded into discotheques and “clubs” as alien new music called electronica, club and techno flourished under a heartbeat of strobe lights.

However, as someone born in the 2000s, that era is before my time. I have no way of understanding the complex musical culture that took place during that decade, aside from musical exploration of my own. I grew up with media that had glimpses of it, and the bits and pieces that I had gleaned from various sources allowed me to construct a facsimile of what I thought culturally encompassed the 90s.

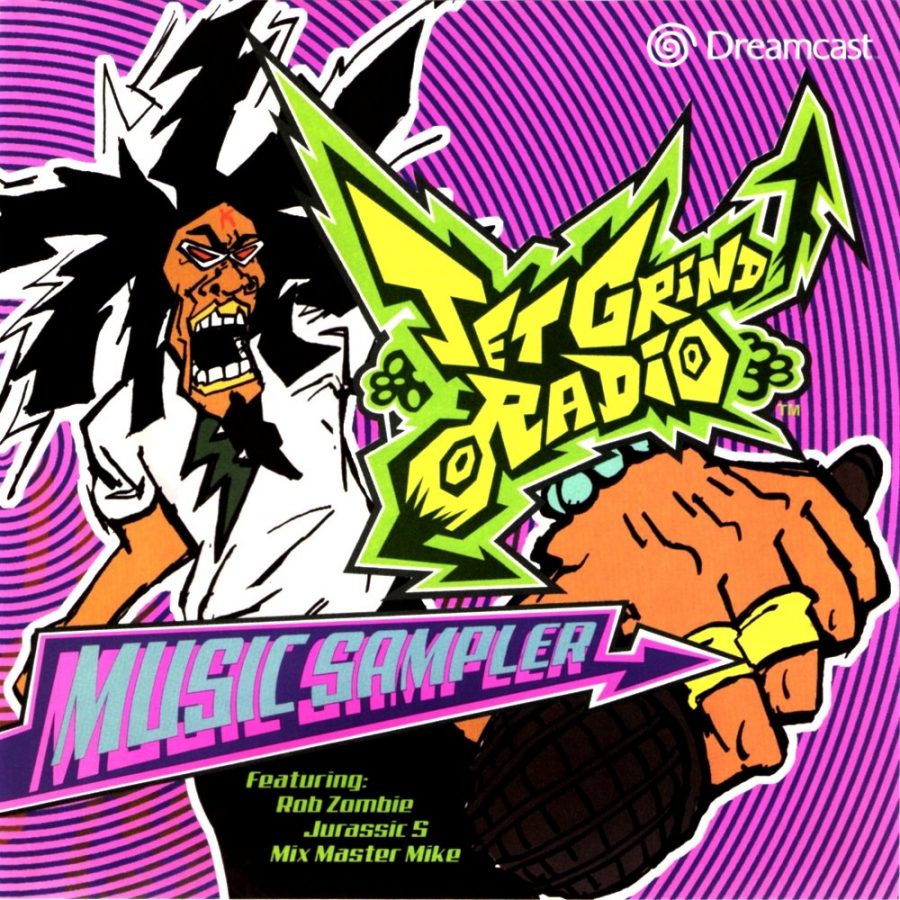

As a giddy child, I’d often accompany my dad to flea markets, and I remember one day, I had bought a strange little title for the Gameboy Advanced called Jet Grind Radio, an isometric-style skating game where the object was to graffiti the entire city of Tokyo-To with your street gang and avoid the cronies of the Rokkaku police state on the cusp of late-stage capitalism.

I had been greeted by this strange little cel-shaded oddity, and this funky little soundtrack of crunched hip hop. At the time, most handheld games from the era of 2010 had still retained the waning chiptune style of the 32-bit era, with straight chiptune or chiptune-influenced rock/orchestral music.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHwkx8w0Ick&list=PLWQigmFvFjPdvjrUyTTkpocV3KHfibXmO&ab_channel=DJTGS

Meanwhile, on this tiny little cartridge was the 30-second looped melodies of hip hop, techno and turntablism. This music that I had recognized as this strangely familiar, yet ephemeral style of music. It was weird, it was insane, it was old and it was new.

I was hooked.

The impulse purchase of the strangest cartridge I’d ever seen had exposed me to obscure genres of music, and it quickly became one of my favorite video games. I had become enamored by this world but a few pixels deep, I fell deeper in love because of this soundtrack. I thought to myself, “what else had I been missing?”

My nimble hands sought google and discovered that the game I had been playing was a remake of this title for the Sega Dreamcast with the same name. Being a console from 1999, I was so engrossed in this game that I had to track one down for myself. I would discover these phenomenal games, like Space Channel 5, Soul Calibur, Chu-Chu Rocket and Crazy Taxi—but no matter how hard I searched at local shops, my “white whale” Jet Grind Radio always eluded me.

Chances are I was the only kid in 2011 asking their parents for a Sega Dreamcast game for Christmas. All my friends were probably asking for the latest Call of Duty, Halo or Pokemon games, but not me. The few days before winter break, my parents surprised me with the game I had been desperately trying to find as an early gift. As a Pokemon kid, there wasn’t really any other title that had entrapped me in its universe before.

This obscure GBA game was, in some ways, the instigator in my love for music. It was the first piece of media that showed me the wildy and zany ways humans can create music that is as conventional as it is unorthodox. It showed me that the radio wasn’t all there was to music, and that genres I couldn’t have imagined existed within the musical underground.

Now, I have a more holistic worldview on both the evolution of music and the history of musical expression and greater American culture. Despite the Jet Set Radio series somehow capturing this paradoxically idyllic yet inaccurate exaggeration of 90s culture, I can’t help but admire it as this time capsule of musical culture, social climate and countercultural thesis in one “last hoorah” to the decade.

In capturing the impossibly complex microcosm of 1990s pop culture, no piece of media is as lighting-in-a-bottle as Sega’s 2000 masterpiece Jet Grind Radio.

In my opinion, the best way to understand the worldbuilding of the game is to take everything you understand about the 90s and insert yourself into its world: Your face is sunburned by the static of the television screen and droning from this electronic soapbox is this virile gospel of MTV and yuppie-manufactured comfort.

In some ways, American culture was never more vibrant. In others, never more bleak. This interesting dichotomy of industrial collapse with the vacuum of the middle class created a disconnect in art that seemed to leach off urban culture. Middle class children with Air Jordan 1s were listening to The Wu-Tang Clan, A Tribe Called Quest, Tupac, N.W.A and The Notorious B.I.G. Somehow, they paradoxically became the audience both most and least appealed to by their trials and tribulations.

The grimy malaise and emotional dissonance of grunge and indie rock made their way onto the airwaves, contrasting the cleanliness of the suburban factories of nuclear families in the American countryside. The middle class schisms of Tommy Hilfiger, Ralph Lauren, and other brands like Guess and Cross Colors seemed to impossibly represent both the upper middle class and the vibrant streets of the dystopian metropolis. American culture was fundamentally together, yet intensely divided.

Each opposing force helped to define the cultural footnotes of the1990s: middle class Americana, the breakout of hip hop, the invasion of rave culture, vibrantly colored clothing, and the rejection of saccharine pop.

It seems impossible to have done so, but Sega somehow captured the sonic microcosm of the 1990s in just a few hours of gameplay. Entrusting the little known producer Hideki Naganuma to create a soundtrack that was as urban as it was suburban, and as American as it was Japanese, Naganuma constructed a visionary musical sampler encompassing alt-rock, grunge, industrial, J-rock, techno, hip hop, turntablism and Shibuya-Kei.

In an age where music traveled almost exclusively by the charts of the Hot 100, people in your local record store, or by the people who were closest to you, Hideki Naganuma and others exposed an unlikely generation to unconventionally infectious music.

The zenith of Jet Set Radio’s worldbuilding isn’t just the enthralling gameplay or the dynamic cel shaded scenery, but rather the soundtrack that contextualizes the game’s physical world.The sample-heavy turntablism of Naganuma’s production are segmented throughout in a way that tonally accents the locations of the game, or ethos of the characters. The four worlds in Jet Set Radio are segmented with their own musical playlists for that specific location, encompassing Kogane-Cho, Shibuya-Cho, Benten-Cho, and Grind City (Grind Square/Bantam Street). The culture of these areas is reflected by the antagonist gangs of these areas, and serve to sonically typecast the design of the area and its characters.

As one of the four subworlds of the game, Kogane-Cho is a grimey yet calm residential district . The amber-tinted skies of the scene give the backdrop of suburban malaise off of the sheet metal roofs. The music reflects the passive restraint of a bedridden-teen, doomed to wear out their tape deck. Reps’ slow burning banger “‘Bout The City” takes a relaxed approach to dance-punk, channeling the energy and sound of Parquet Courts nearly two decades before Wide Awake!. Naganuma’s energetic and infectiously screamed opening on “Rock It On” warps the listener to an impossible turntablism DJ set.

He brilliantly channels its expansive synth lead as the stitchwork between alt rock and hip hop, blending the two genres into a dark and gritty quilt. Guitar Vader’s “Magical Girl” and “Super Brothers” foreshadow the impending garage rock revolution of The White Stripes with blown-out chords and punch-drunk drumming, while maintaining the slick progression and production idiosyncrasies of Japanese power pop bands such as The Pillows.

The rivals of the area, Poison Jam, are rowdy misfit teens, presumably from the housing sprawl they lurk in. They are the neighborhood bullies—these imposing gruff, tough “big kids” who at the end of the day, still go back home like you or I. The craft room costumes highlight the simple and relaxed disposition of suburbia as they swerve from the rooftops and into the asphalt below. The sunset over the water evokes youthful afternoons after school, discovering alt-rock for the first time, and finding your uniqueness among a bastion of cookie-cutter complacency.

Suburbia isn’t the only residence explored throughout Jet Set Radio. Benten-Cho is a center of urban sprawl and static. Both a downtown and entertainment district, the halogen blue radiating off of the high rises and shop windows give the image of a city at night, teeming with life. Benten is ruled by the Noise Tanks, a group of jumpsuit-clad cyborg wannabes who “sell software to pay for their graffiti”.

The Noise Tanks ensure with their electronic rigidity that the player will boogie down with hip-house tracks reminiscent of King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard’s “Cyboogie.” The slow burning dance-punk and angsty J-rock have been forgone for the mechanical rhythms of techno and unrestrained electronic breakbeat.

Naganuma has taken the back seat for this section of the game, and enlists the production of Deavid Soul. The textures become much more synth-heavy, with more lo-fi and urban tones transcending into a dancefloor of wingtip-skidded pavement. Tracks like “Miller Ball Breakers”, “Yappie Feet”, “On the Bowl ” and “Up-Set Attack” are wonderful symphonies of hip-house whose arcade coin-slot-aesthetic and runaway-convict-energy guide your character through the police guarded streets and subways. Their perfect synergy of sample-heavy eclecticism and punchy house beats ensure that, whether you want to or not, a disco is going on inside your head. F-Fields’ “Yellow Bream” manages to combine the jagged chords of alt rock and power pop, with the stammered keys of a house 12” club-banger.

Toronto’s “Electric Toothbrush” is a minimalist/acid techno track that manages to become a parasitic earworm with its simple, yet catchy melody. The standard drums with the grainy synth lead give way to a groovy and smooth chiptune melody. The electronic oversaturation of these rave reject tracks compose themselves perfectly for a lively city at night and the incandescent basements below.

The bridge between suburbia and the urban environment is created by the overarching culture of consumerism. Shibuya-Cho is the commercial shopping district of the game, self-referential to the (nearly) same area in Japan. The enemy gang in this area is the Love Shockers. These fluorescent gothic mall-rats wouldn’t look out of place in the parking lot of the shopping center two cities over or causing hijinks in the streets.

Shibuya-Cho is the first location in the game that you encounter, encompassing some of the game’s most iconic tracks. Many of the cuts from this area are the most jovial and playful in the entire catalogue. Contrasting the alt-rock of Kogane-Cho and the electronica of Benten-Cho, Shibuya is primarily hip hop turntablism, with Japanese pop flairs.

The stumbling bustle of keyboards on Idol Taxi’s “O.K. !? House!!!!!?????” makes the most chaotic and bouncy track in the game. This auditory tongue twister has wonky, collapsing vocals and a staggered structure that picks up bits and pieces at mercy of the rhythm. The off-kilter fun displayed on this track and others repeatedly demonstrates Jet Set Radio’s genius. Richard Jacque’s “Everybody Jump Around” has become somewhat of an unofficial anthem for the game. It’s a masterful vocal sample of House of Pain’s “Jump Around,” making it the most contagious cut on a robustly danceable soundtrack. These squawking, jangly guitars in “Sneakman” erupt in an energizing hook of infectious crate-dug magic. “Sweet Soul Brother” brilliantly frankensteins forgotten vocal samples into a melodic and funky excursion. Its clap-led rhythm commands you to do the very same each time the song plays.

The areas removed from the primarily Japanese aspects of the soundtrack are the most overtly American tracks in the series. These areas are genericisms of inner-city America, with Grind Square being a play on Times Square and Bantam Street resembling a more residential offshoot of Chicago. The tracklist for these areas represent the popular musical culture in the United States around that era. The tracks are a bombastic mix of everything from boom bap and American textures of turntablism, to the nu/alt-metal styles that had gained popularity during the latter portion of the 1990’s.

The sparse bass and cacophonous snaps of Jurassic 5’s “Improvise” plays during the scene preceding the first playthrough of these areas. You glide from the above-ground subway to the concrete below, finding yourself in this oddly familiar urban backdrop. An array of shops and a gas station nestle themselves between the compacted city blocks. Long-gone are any footnotes of Japanese culture or iconography. Hideki Naganuma, Deavid Soul and Richard Jaques’ turntablism has been foregone for a much more direct sound. MCs in baggy clothing on street corners become a much more evocative image than the club experimentalism of hip hop snobbery. These levels are more raw and dystopian in their presentation compared to their Japanese counterparts.

Mix Master Mike’s “Patrol Knob” is a break-beat, horror-core triumph that digitizes the sound of Cypress Hill and the most dissonant echoes of the Beastie Boys into a cyberpunk trunk-knocker. The transition from police enforcement into heavy artillery to combat the players is perfectly matched by the blaring chords of Rob Zombie’s “Dragula.” The jovial tinges and playful atmosphere becomes extinguished as the tracklist becomes heavier. This isn’t a game anymore. Not long after, the player learns why characters Cube and Combo left Grind City.

You make your way to Grind Square, but something is off. The charming and colorful advertisements have been replaced by grotesque and bleak propaganda. The saturated fog of color is but restrained to a few screens, being swallowed by Stalinist high rises of grey and black. What was once a small town police officer on your tail has been replaced by a gestapo. The music becomes as high stakes as the gameplay, with the nocturnal hip hop morphing into alt rock and alt metal. The frantic strumming of Professional Murder Music’s “Slow” reinforces the isolation and detachment your gang faces. This bitter longing is further echoed by Cool’s “Just Got Wicked,” whose fractured effects and tool-derivative singing cement that it’s truly just you versus the world. This disillusionment, though not suffocating, is a wonderful portrayal of systemic rejection, and the steps that one can go through to change something that is fundamentally against them.

After you’ve dealt with the entirety of the Rokakku group, you’re tasked with facing the final boss of the game, Rokakku himself. You meet across a skyscraper, rotating on a giant record. Women are dancing in cages, vaguely similar to the circling “Demon Hipster Chicks” of Scott Pilgrim’s Matthew Patel. The soundtrack’s most eerie, sinister and downright fucked-up bop shows itself—“Grace and Glory.” You’re in the endgame. Twisted operatic screams seem to slither around your body in a asphyxiating coil. Underlying pummels of trance drums punch themselves through the laughter, groans and screams, metastasizing into a club-banger that is as grotesque and alluring as Tetsuo’s Akira. You defeat Goji Rokkaku and have liberated Tokyo-To. The credits begin to roll.

Restoring the bright and vibrant atmosphere of the earlier levels, you are treated to the series mascot Beat skating around Shibuya-Cho, tagging “Thanks for playing” to a megamix of the game’s tracks.

Sega showed that, in the immediacy of the 1990s, it was a vibrant time for music and painted the urban setting as this untamed beast of creation—a counterpoint to its disrepair and vacancy. Through Naganuma’s companion soundtrack, they were able to construct a world that was almost as colorful as the pop culture predilections of the decade.

Jet Set Radio encapsulates its era’s cultural footnotes so perfectly that it is as dated as it is modern. The fluorescent neon of the night and day is perfectly illustrated by the seismic and groovy tracks, each showcasing a swatch of urbanization: Grainy yet infectious hip hop beats that carve themselves into your skull like a tag on a subway window, dingy, shaggy-strummed alt rock riffs and its ensuing influence on Japanese rock, an incandescent, pulsating miasma of electronica and the techno revolution that shook the night. Naganuma and the sound design team brought together a swirling maelstrom of various sounds into one of the most potent distillations of a cultural era that I have ever seen in a single piece of media. I’m not quite sure if that was the intention, but Jet Set Radio has become much larger than Naganuma or Sega could’ve ever hoped; It’s powerfully retrospective, poignantly prophetic, and pop-culturally timeless.

The streets are calling. Will you come out to play?