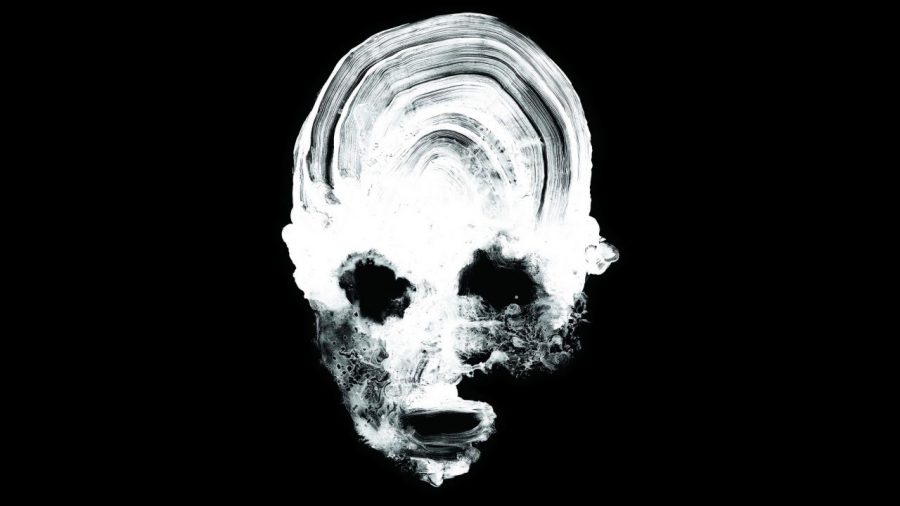

Daughters Interview (March 9, 2019)

February 26, 2020

Editors Note: On Oct. 12, 2021, Kristin Hayter, also known as Lingua Ignota, came forward with allegations of abuse from her previous relationship with Marshall. In a thread on Twitter, Hayter noted Marshall’s reputation wasn’t a secret in the industry and said his abuse was the subject matter of her most recent album, Sinner Get Ready.

Throughout the latter part of the 20th century and into the 2000s, the smoldering ashes of the Washington D.C. hardcore scene began to fan the flames of new musical fires. New acts encompassing influences of math rock, emotional hardcore, grindcore and metalcore began to slowly rise from the ashes and populate the metropolitan epicenters of the U.S. New scenes were metastasizing across the east coast and into the Midwest, drifting from the ground zero of Washington, D.C.

Daughters is a band hailing from the city of Providence, Rhode Island. Notorious for their involvement in the microcosm of eastern hardcore, after eight long years since their self-titled farewell, they have reformed and released 2018’s You Won’t Get What You Want, to critical acclaim.

On a rainy, cold day in the winter of 2019, I had the chance to interview frontman Alexis S.F. Marshall. Under the overcast sky at Ferndale’s Loving Touch, Marshall recants his brazen youth in the ‘90s Providence metalcore scene, his band’s new record, and the personal growth the new century brought, for better, or for worse.

MC: So, who are you? Who is Alexis S.F. Marshall?

AM: I just told you he was some jerk in a band?

Some jerk in a band named Daughters?

[Laughs] I, uh, just play music.

What led you to making music initially?

I was singing in the mirror as a kid, you know, stuff like that – making up words to songs on the radio. I always liked singing, I didn’t think of it as a real career. I wanted to play soccer in junior high, then I got into drugs. And then I realized that it’s hard to do drugs and play sports, so I realized I should play music. You can do drugs and play music – easy. But now I’m sober, 10 years.

Your lyrics are very poetic in nature. Did you start writing personally, and then use music as a vessel or medium to further your own expression?

I was writing songs initially, and then we can only have so many songs. And you can only do so many parts of a song after so many times. So then I would start writing to songs that didn’t exist and I was writing for songs that didn’t have music. It was sort of a realization that I didn’t need the band to write. And that’s been a great discovery for myself.

Furthering that sense, your lyrics are quite grotesque in their imagery, like the inescapable blunt of Allen Ginsberg or Jack Kerouac. Not necessarily these writers, but who would you say influenced you the most when it comes to writing, be it songs or poetry?

Oh, I don’t know. There are poets I admire like Philip Levine, Charkes Semic. There are lyricists I think are great: Tom Waits, Nick Cave tells great stories, Leonard Cohen – writings I think whose stories you can get lost in, remove them from music.

I was working at a record store in 2006, and we got an import of the Nick Cave collective mix. I picked it up, bought it, and was a fan. And that’s when I realized with lyrics that removing them is not fucking easy, in a literary sense. And I think that was pretty great.

Were there any specific records that have meaning for you that you encountered at that store?

More so when I was younger, and that’s how we did it pre-Internet. We had to discover bands some way, so we’d buy records. And then that band would thank two dozen other bands, and then you’d buy those bands records. Some of them made for a terrible listening experience, and others were great. As of late, I can’t really think of any; sometimes I get in a mood and listen to The Sparks for six months.

When you write, either poetry or song lyrics, do you tend to self reflect and use preexisting viewpoints that you have to roughly outline your narrative? Or is the bulk of your work a spontaneous moment of fervent writing?

When I’m writing songs for Daughters, it’s more the latter. It’s not necessarily specific to that situation, it’s maybe what I’m feeling. Or I think of a line with some wordplay that I enjoy, and I’ll build off of that. And then I’ll just create it in the writing process. Also I walk when I’m writing for Daughters, and I don’t do that when I’m writing for other aspects; it’s much more of a physical process.

If I’m writing poetry however, I’m reflecting upon some instance in my life or something. It’s easier to do that because it’s personal, so I don’t have to think of anybody else, I can just think about myself. With the band, I try not to write about anything that is my sociopolitical ideology, so I have to write stuff based on what John or Nick might not agree with. In that sense, it’s my writing but it’s our band.

It’s scary. It’s like I’ve been playing with these people for so long that the thought of my words without these people to lean on was quite daunting, but now it’s quite liberating.

For your writing process you said that you pace around. Do you walk around your house or back and forth around town?

I kinda walk around the house. I’ll start there and put my notebook on the table – wander around, try and flesh things out. I don’t go for any walks or anything like that or clear my palate. I just set up to do it and do it in a proper setting.

Your current work with Daughters and musical past was born from the grindcore/mathcore scene that rose along the Eastern Seaboard in the late ‘90s and early 2000s. To you, was this music “experimental” at all? Or was it this shared ideology in music that swept you up?

I think fondly of that. Things that are called grindcore and mathcore, those were not really a term any of us used back then. I think there was a really deep well for everyone to take from, and everybody played together. We’d play shows together with hardcore bands in Providence. There’s this old band called Nowhere Fast that we played with all the time. And we played whatever pseudo-metal nonsense we had at the time. I’d go around to shows and see Overcast or 25 Ta Life, and there were so many different genres it wasn’t weird.

Everyone can fit into a variation of a variation of a variation, and we never were concerned with what we were categorized as back then. Everyone would play together and hang out, and it wasn’t a big deal. I’m not bothered by “genre” now, but I suppose I was ignorant to it back then, as everything was communal in the ‘90s. That was sort of the last era of that kind of “post-hardcore” and “post-punk” or whatever you could call it, coming off the heels of the very stringent lines of hardcore. You’d have New York hardcore, Boston hardcore. It was really the same thing: it was tribalism. I think we were in a nice place, and everyone wanted to be an emo or screamo band, everyone had a style and it was divisive ultimately. I’m thankful that we made it through the ‘90s and into the 2000s.

Especially with the advent of the Internet, there’s definitely a sort of homogeneity with the music that is created now because of the unprecedented level of access.

A lot of people want to say “it’s this.” That band, they’re this kind of band, [and] they sound like these two other bands. I’m happy that we’ve escaped that trap and that if people want to know what Daughters sound like they have to listen to us. There isn’t really a way for people to explain who we are.

Experimental is a buzzword that’s tossed around. Would you consider the work with Daughters as of late “experimental”? Or would you say that’s more or less people attempting to categorize the music scene when it’s evolving too fast for them to keep up?

I think what people consider experimental is not experimental at all. I think experimentation in music almost solely exists in the classical and jazz world, and everyone else is trying to evolve in some way. I don’t think that there’s a lot of superbly interesting experimental music happening – certainly not in the pop world, not in what we consider “modern hip hop,” and not in hardcore– not in any of it. Nobody in the forefront of what we consider musical genres is doing anything that’s going to change anything culturally; those days are over. We’re not going to see any more Rolling Stones or Beatles come along and change the culture. You know people like Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Elvis? They “did it” and now everyone else is trying to catch up, or hoping to simply achieve that and not necessarily expand on it.

I think artists who do something important are true to themselves in some sense and not particularly interested in what people are doing or what they’ve been. I don’t know if we experiment. We try to take different routes, we try to keep ourselves interesting, and maybe the people who we’ll confuse are evolution in experimentation. But we’re not a band that worried about being “experimental” in the sense of playing tin cans, shopping carts or other wild shit. Those bands are pushing music in new directions, and when they do that for a while, everyone catches on and it becomes the norm. But I think it’s rare that people nowadays genuinely “experiment” with music.

Would you therefore consider the notion of experimentalism a product of the present?

I think it’s all open to interpretation.

If you look at what was considered experimental, it’s almost a “trend” with how the world reacts. In the 1960s you had Brian Wilson and the Phil Spector wall of sound, which was very influential in the coming decades of production. Back then, production that lush was considered very experimental. Now, a lot of the techniques that were once experimental, are more or less commonplace in the sphere of modern music. So is experimentalism moot in and of itself?

Yeah, Jesus. I mean on Pet Sounds you had literal animal noises on the record, which was absurd and unheard of at the time; Brian Wilson was a genius in that sense. I just think that everything that becomes new becomes normalized, and therefore accessible. Most of that is because of the Internet, which can be great, but can also take the excitement out of discovery. I wouldn’t cancel it all out and make such a statement like “nothing is truly experimental anymore,” but true “experimentalism” is rare – as it should be.

A lot of people want to get involved with it because they want to become famous, or that music is everywhere. It’s in Coke commercials, so you just turn it on and it’s there. It’s not like the sense where to digest it, you’d have to go out to a museum or something like a painting. You go into Target and it’s just playing. It’s an easy platform where anyone just thinks they can get involved. I see for example, you have “Instagram poetry” where everyone thinks that they can write poetry now, and write their kind of bathroom thoughts: fortune cookie metaphors that they have and they suddenly think that they’re poets. Accessibility is something that allows non-creative people an attempt to be creative, which is fine. Everyone should be able to access that portion of themselves, but with everything so accessible, people are kind of diluting the pool and lying to themselves that they are doing something of interest.

I remember listening to SMiLE sessions, the archival tapes of Brian Wilson’s SMiLE, which he thought was complete garbage. Nowadays modern music under the blanket term of experimental can seemingly be just a simple diversion or offshoot from the traditional way. If you go back and reference those tapes, even by today’s standard, music of that structure and complexity is still unheard of.

A lot of people just don’t get it in the sense. I was working at a record store, and we were playing a Swans record. I had someone ask what it was and I don’t remember what we were playing, I think it was Soundtracks for the Blind. He just said “oh, well I don’t get it,” and to me, it’s not a math problem like everyone thinks it is.

Your bands latest record, You Won’t Get What You Want, is seemingly inspired by no-wave. Did you consciously want to make a record of that abrasive nature, akin to Swans, Sonic Youth, Foetus, and the parallels between no-wave and grindcore? Or was it a natural path congruent with the evolution of your sound?

After eight years, there’s a big leap in that sort of evolutionary process. We haven’t done anything in so long that a lot was happening everywhere within that time frame. Nick was working a lot with film scoring, and was really inspired by the process there. I think the two of us, with what I was writing and what Nick was writing, it was really working out and it was great. I think we met in a great spot where what we were working on separately was complimenting the other and I don’t think we were writing with each other in mind. It was just sort of this really lovely chance that things happened the way it did, and this new record has this really great atmosphere and manic feel to it.

Looking back you can see the huge leap, but in part it was what we were experiencing through life and it was important to us. Daughters isn’t a particular band like Slayer is a type of band; our view and interpretation of music changes over time. It’s a nice flow, and we’re not chained or anchored anywhere. We do whatever we want to and it’s a nice feeling. In hindsight you can look at the old catalogue and say “what the hell happened?” but the progression is definitely there. I feel like if we went off the handle and did something different, every record it would seem a little forced or insincere.

It’s funny, I find You Won’t Get What You Want almost human in its dark recesses. I don’t think you made this album to be a sort of statement on the mind when it goes berserk, but it’s almost powerfully relateable in the depths of depravity that exist within ourselves as an almost fantasia of power. Why choose this as the thesis behind the album?

I think that’s accurate, yeah. That’s sort of my general attitude and my thinking process just in my life where there’s always a constant question of “what am I?” especially as a parent, like “am I going to be my father?”

I mean, I hated my father so it’s more so “are my children going to hate me?” So life is sort of a constant river of dread and anxiety that I’m going through, on top of the anxiety and depressive episodes I have. So yeah, that’s sort of what I was writing about. Do I question whether any of us really deserve to be here? Yeah I do. I think about that all the time, I think it’s reflective and the lyrical content… Yeah.

I think one of the most hauntingly cryptic lyrics on your new record is “Today’s gonna look like tomorrow some say / Tomorrow’s gonna feel like yesterday.” Is that a whole notion on the cyclical nature of life and the fantasy of power that we all wish to grasp?

Yeah. Nick and I were talking about that line the other day, and Nick never asks me about lyrical content. We were talking about that line and I told him I wasn’t exactly sure what I was saying. He said “Well, it’s good wordplay,” and I said, “Yeah, it is good wordplay.” But it’s sort of the interpretation of time and how we apply it to a life and how we create our timeline and base our emotions and feelings within ourselves. If this was a bad year, people say “2018 wasn’t my year!” That’s just an absurd notion that the year has done something bad to you and how we function sort of “in the moment.” It can be monotonous, and it can also be exciting from one moment to the next.

And what does that mean, and does it even matter at the end of our lives? Does it even fucking matter? Does it even mean anything at all? Days are days and they come and go, we just live in this moment. Tomorrow is going to be today. Today is never going to be yesterday, never going to be tomorrow either. Everyone lives in the moment and thinks that they can create a five-year plan. The guy who got hit by a bus had a five-year plan, and then they’re dead, that’s it. The days just kind of blend.

I find that joy is fun and all, but it really doesn’t tell you anything about yourself. I think that when we fall into some bleak dark hole, that there’s some self-discovery there, and it’s where we start asking questions. Nobody asks questions about themselves when they’re smiling. Sometimes I see people who are always happy, and I wonder “what’s really going on?”

You Won’t Get What You Want has been met with unanimous critical acclaim. It was given a perfect score by The Needle Drop’s Anthony Fantano, an 8.0 on Pitchfork, a weighted 87/100 on Metacritic and currently holds the top spot of Album of the Year on RateYourMusic. Were you surprised at all by its strong reception? I’m sure it’s surreal in a sense as a songwriter in that you primarily make art for fun.

We didn’t have any expectations, we called the record You Won’t Get What You Want to not have any expectations from us – especially since it’s a lot of pressure after eight years. It’s also a reminder to ourselves, we should feel obligated in our own right, because we’ve never gotten good reviews. Nobody was ever interested in what we were doing. We always existed as kind of outliers, and played shows and maybe people came to see us because they like the band we were playing with, or they wanted to see some spectacle where I would drink alcohol out of a shoe or get naked on stage. So, to receive so much praise is nice – it fills the rooms – but it doesn’t affect us beyond our accessibility to find more people. And that’s great; we want to find as many people to listen to us as we can, but we’re creating a vacuum for ourselves just with each other all the time. We did the last tour in November, and when I got home and the record came out and we got all these reviews, I thought to myself, “This is gonna sink in at some point and everything’s gonna feel different.”

Life is just life and it didn’t feel like anything. We came back out and yeah, the rooms are bigger, we were selling more and that’s great. You know hopefully that’ll keep us where we can continue to do this if people are interested in it. If people weren’t interested we wouldn’t be able to go out and play. But yeah, I reckon that we’d still continue to make music, whether we’re together or apart.

Do you see yourself making more music, or is it very much a creative binge for you? And in these sparks of creative production, does an album or work of yours takes shape?

I’m always writing, Nick is always writing. We’ve been talking on this tour for the record. This is a North American tour, our first “full” tour, and we’ve been talking about doing the next record and all the ideas he has for everything. We’re just constantly making, and you sit idle and Christ, how long did Hatebreed tour for Satisfaction is the Death of Desire? Like six years? It’s just like, I don’t want to play these goddamn songs for six years. We have songs we haven’t played in more than 10 years and we’re playing them. We need some more songs to get these olds one out of here. We don’t give a damn about them anymore, so even at this point the tour is like “God this fucking song again.” We’re just trying to keep ourselves interested, because if we’re not interested in it, what the hell are we doing here? If it’s not fun then we might as well just go home. This is supposed to be like “better than a job,” and this is my job now, but it’s not like you punch to clock in and answer to some boss with a dress code, so this is great.

It’s probably even more surreal after gaining this large amount of acclaim and success for the album that you made. From a naïve point of view, having a “good” album can make artists feel validated as a benchmark for success, but it can sort of evolve to where you don’t want to be remembered as the band that made “that album.”

That’s a dangerous way of thinking; you can write anything that you want, [but] that doesn’t mean that people are going to want to care or listen. People are fickle and they’ll enjoy something as long as it’s in vogue. Then they’ll grow out of it, so to speak. We have no control over whether everyone decides that this is a good thing, Fantano gives us a 10, everyone wants to listen and everyone gets over us – that’s up to them. We’re not gonna cry about it, and we’re certainly not going to adjust our artistic ideology to dictate what we’re doing.

We are appreciative of all the good reception, but it’s really incidental. If we’re making “good” art and people want to participate, view and listen – that’s wonderful. If they don’t, that’s up to them. We can’t do more than that and we can’t force it. That’s what killed music: some garbage like Britney Spears or that boy band nonsense in the ‘80s and ‘90s. That stuff was just “let’s manufacture this stuff and sell it.” Who cares? I don’t have any interest in taking part in that.

This aspect of commercialism that really consumed music for the first time since the ‘60s, it definitely helped independent and underground scenes into the limelight because of the persistent fodder shoved into our troughs that we eventually became self aware too.

You have to pay for music and you have to pay for art. It is by nature a product. But how we internalize it is up to us, and that’s more important than anything else. You can write a great record that doesn’t sell, but that doesn’t change the quality of what is inherently within the record, or whatever it is, like any painting.

People can discover things far long after the creator is gone, and that is a beautiful thing about art in some sense. You know, once you create it and put it out there, it’s not really yours anymore; it’s for everyone else. Especially with music, or with my writing, people read something and internalize it, and decide that it means this to them, and they hold onto that. You can’t deny that or take that away from them. Maybe that’s not what I intended. Someone decided it means this to them in some way, or upset them in another way.

Because of that I wouldn’t even attempt to define myself in any way. We’re just gonna play music and write what we like… When I look back at Canada Songs, I just think “this did not age well,” but people want to hear it. I don’t know why. I wrote this when I was 21 years old, and I’m almost 40. I don’t see any artistic merit in what we were doing. So, it’s always changing, and what can you do?

You can listen to their newest record, You Wont Get What You Want on all streaming services via Ipecac Records.