At least twice a month in the Lansing area, an otherwise unassuming basement becomes—to the average person—a warzone. But for the regular patrons of venues like Montie House or The Jolly Llama, the chugging guitars, harsh vocals and torrent of fists are a home and a much-needed break from everyday life.

Many such show-goers are Michigan State University students, including Impact 89FM’s own Aaron Kasuba (AKA DJ Suba), co-host of Pity Party.

“When I started going to MSU I wasn’t super interested in parties, but I loved going to DIY shows. That’s when I attended my first hardcore show at Montie House.”

That path was also followed by MSU Zoology major Fish Smith, who’s spent the last three and a half years promoting local shows on his Instagram.

“I don’t just post hardcore or metal there, and I don’t post as often as I’d like sometimes,” Smith said. “But I’ve heard some people say they’ve made it to shows they didn’t know about because of it, which makes me happy every time.”

Sean Dusk, member of bands Self Absorbed, Feign and Dear Heretic, has always called Lansing his home.

“[I] stayed here because the greater music community is great and I’ve made so many friends. I would never want to leave.”

Kasuba, Smith and Dusk are all part of the Mid-Michigan Hardcore Collective (MMHCC), a group of over 30 people who, in the past year, have committed to sustaining the Lansing hardcore community. The MMHCC was born from the desire for a Lansing music scene beyond the emo groups that emerged just after the pandemic.

But what was the scene like before COVID’s hard reset?

A Hardcore History Lesson

If you want to know anything about the beginnings of Lansing punk, look to Tesco Vee and Dave Stimson. In the late 1970s, the Williamston residents spent their time scouring record stores—including East Lansing’s own Flat, Black, and Circular—for obscure punk and punk-adjacent records to review in their zine, Touch and Go.

Touch and Go touched those in the budding hardcore scene nationwide, including the likes of Black Flag, Teen Idles and Ian Mackaye of Minor Threat. By 1981, Touch and Go had grown into a small label with bands such as The Necros, The Fix and Negative Approach in their lineup.

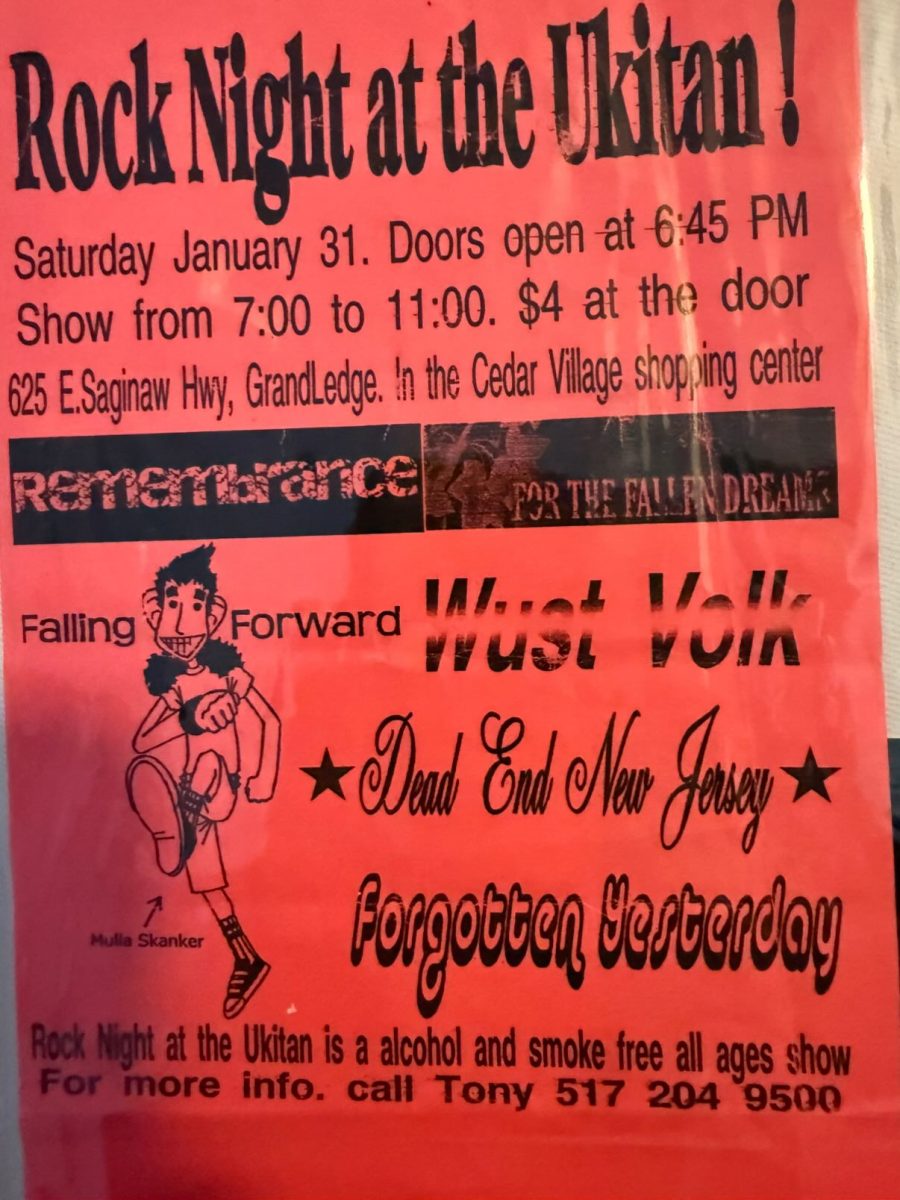

Flash forward 30 or so years. The Lansing Underground of yore is dead. Jacob Weston is at a show in a Grand Ledge tanning salon.

Weston was born in Lansing and still lives here, which is what he credits to keeping him in the hardcore community since he was a young teenager. He says of the tanning salon:

“They would move everything out of a side room and let bands set up there. My eighth-grade band played there a lot because we could flyer to all the kids in Grand Ledge and it was just a cool little hang out.”

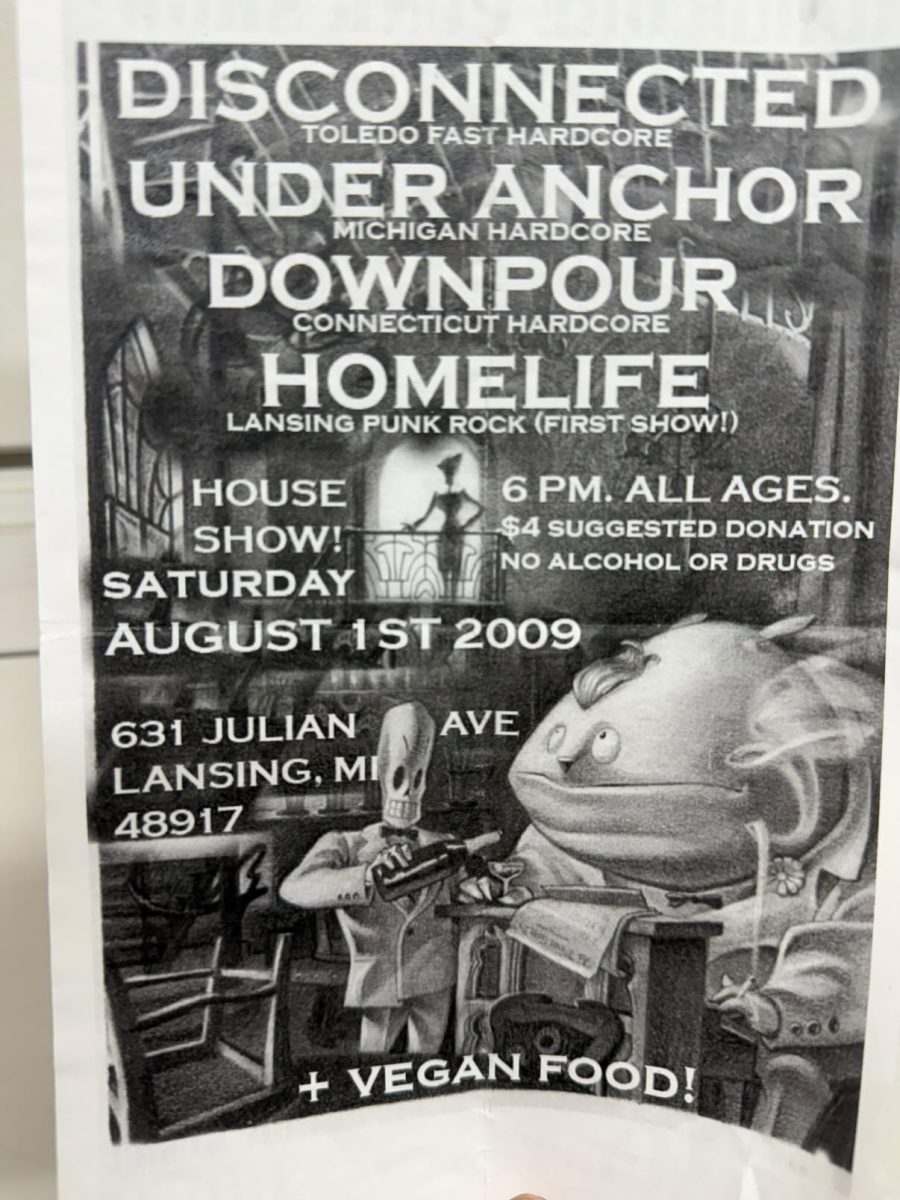

In the early 2000s, you wouldn’t be hard-pressed to find a pop-punk show in an odd spot; a product of folks piecing together what was left of the area’s DIY spirit. But by the late 2000’s, people knew what they wanted. Weston and his crew started booking hardcore shows themselves, at Weston’s basement, Mac’s Bar or even MSU’s own Snyder/Phillips Hall.

“In a lot of ways, that still feels the same. It’s just a new generation doing it their way, in their spaces.”

Today, Weston plays in two bands, Drop Rate and Silktail. He also runs a label, Setterwind Records, with friend Luke LaFountain. Setterwind has a healthy lineup of local artists in an array of genres. It’s a path that just makes sense for Weston, who has ample experience with getting up-and-coming musicians connected.

“I currently have two kids under 10, so show-going is limited compared to what it used to be. I still get out and support as much as I can and help promote things going on through social media.”

Emma Miller, MMHCC founder, went to her first local DIY show on December 23rd, 2011. A second-shift job shortly stole her attention, but she then found a place in the metal scene, going to shows at The Loft, Mac’s Bar and The Blackened Moon. Those venues made Lansing a destination for bands like We Came As Romans, The Acacia Strain and Cattle Decapitation. Miller liked it because she didn’t have to leave her hometown to go to a big gig.

In 2019, she returned to a DIY scene that was still hanging on with the help of house venue Displaced Manor.

“Once my nose got broken the first time, I was hooked.”

After Miller found hardcore, she started dreaming big; of cities like Detroit with ample opportunity. However, when the pandemic stalled out the Lansing scene, she began to recognize the loyalty aspect of hardcore. Staying true to her hometown and helping rebuild DIY was more important to her.

“Watching it grow back after COVID makes me so happy,” Miller said. “It makes me emotional to think we, as a community, did this.”

Now, Miller is at every Lansing show, even booking some at The Jolly Llama, a house venue on Lansing’s south side.

“When it comes to booking and consistency,” Weston said, “what MMHCC is doing now might be the largest group of kids who are committed to building and creating something special here.”

A Mind Behind the Mayhem

The aforementioned Montie House is one of many co-ops that have opened their doors to local music. But Montie’s basement has set itself apart as an institution in Lansing hardcore, thanks to the efforts of Abi Mayhem of Mayhem Booking.

Mayhem is an MSU alum. After graduating in 2021, she relocated to her hometown of Kalamazoo, where she became acquainted with the DIY scene.

She moved back to Lansing a year later and started attending shows at The Goblin Zone and The Church of Elvis Presley. There, she found a community, and a best friend in Dusk. In March of 2023, he invited her to her first hardcore show. She then impulsively attended Detroit’s annual hardcore festival, Tied Down, and the rest is history.

“I have a small and wonderful group of people in MMHCC that help set up and clean up, but I do all the organizing,” Mayhem said of the shows she books. “The best way to get anything done in the world is to do it yourself.”

But what she does involves more than knowing a couple of bands. It boils down to five things: a date, a venue, talent, equipment, and patience. There are steps to this recipe, too, but it was only with time Mayhem learned them.

“There’s so much of it that I feel like people don’t think about. When you’re thinking about bands, you have to think about pull. Set order should consider how far bands have to drive.

“People don’t think about the fact that I need to clean up after shows and throw their trash all over the ground.”

Much of Mayhem’s time and money is invested into this project. The little things, like free earplugs and water, often come out of her own pocket.

“There’s only been 2-3 shows where I haven’t had to use at least a little bit of my own money to pay bands,” Mayhem said. “I want to make sure no [band] leaves with less than $70. A touring or out-of-state band gets at least $100.”

Mayhem credits the fortune of being able to cover some expenses herself for keeping admission costs low. However, while she won’t turn anyone away, she stopped advertising her shows as pay-what-you-can to stay afloat.

“With the college audience, a lot of people were reading that as ‘for free’. I was that dude for a long time, but that was because I wasn’t thinking about how much went into it.”

Mayhem Booking shows are staying accessible despite the change; growing, even. The first show in the Montie basement was 50 of Mayhem’s friends and a bunch of non-local bands. Now, about a quarter of the people that come to shows are folks she has never met. And, to Mayhem’s delight, the newbies are staying for the show and then some.

“I used to warn some of the ‘random’ people that they may not like what they’re about to head into, but now I just take the $5 and see what happens. There was a Banana Bar Crawl at the same time as a show, and these six girls dressed as bananas came in, stayed for the whole show and bought merch.”

Despite all the challenges booking shows comes with—lack of profit, rejection and creepy dudes among others—Mayhem said seeing her work change lives cancels it out. Two months ago, she received a message from someone who decided to go to Lansing Community College specifically because they wanted to be close to the community found at local shows like hers.

“The DIY scene, even when it wasn’t hardcore, gave me a place to be and feel comfortable. To hear that other people take the same thing away from Montie is rewarding.”

Growing Pains

Hardcore has reach beyond the underground. It’s had some exposure through professional wrestling shows like WWE and AEW, from commissioned entrance music to entire gimmicks, such as CM Punk’s straight edge attitude.

Bands like Kubali Khan TX and Speed gained popularity from viral moments at shows. And who could forget the Denny’s Grand Slam, a hardcore show that is often imitated, but never duplicated?

Kentucky’s Knocked Loose performed on Jimmy Kimmel Live! and received a Grammy nomination for their single “Suffocate” featuring Poppy. The genre has been no stranger to acclaim in recent years: Turnstile was nominated for best metal performance in 2023, and Code Orange in both 2021 and 2018. The former even had a song featured in a Taco Bell commercial, and so did California group Scowl.

The mainstream breakthrough of hardcore has garnered mixed opinions among those on the frontlines of local scenes.

Mayhem said she can’t be mad at bands for achieving the dream of making it big, but some of the moves made with newfound fame go against the ethos of hardcore. Partnering with multi-billion-dollar corporations, for example, isn’t “being recognized”, it’s selling out.

There are also concerns about the intentions of those joining the crowd.

“Those who want to be a part of the scene have to learn about what hardcore actually is,” said Kasuba.

Dusk has a level of appreciation for the influx of newcomers, as he was once one of them. However, some new faces are what he referred to as “tourists:” folks who have off-base ideas about what hardcore should be and want to change it to fit the mold. He shares a common mantra in the scene:

“Hardcore is open to everyone, but it isn’t for everyone.”

Ultimately, it seems the sentiment—even among those with concerns—is that good will prevail over evil. In other words, those who hardcore isn’t for will realize that rather quickly. But more exposure overall means a higher chance for a new batch of tried-and-true hardcore kids to be born. It’s a net positive.

“I feel like a lot of the growth is organic,” said Smith. “But honestly, I don’t think people who come to gawk last as long as people worry about.”

Weston is excited about what more attention means for hardcore, from the late-night stages to the dingy basements. It’s less a sign of distance, but rather that hard work is paying off. All of this effort creates new interest and, therefore, sustains local scenes.

So, let’s say you just saw Knocked Loose on TV. Maybe that caused you to go down a YouTube rabbit hole of Hate5Six videos, which led you to the HardLore podcast, and now you want to go to your first, real-life, DIY hardcore show. What do you need to know? What is hardcore, to those who have experienced it beyond the camera lens?

Kasuba: “Hardcore is a release of pent-up energy. It’s an outlet for those who need to express their anger in a ‘safe’ space.”

Dusk: “Hardcore is community first and foremost. It’s about people coming together to enjoy the music, dance and mosh as an outlet or just for the fun of it. It’s so much more than just an audience watching a band play.”

Smith: “If someone’s knocked down, pick them up. Damage should be collateral, not intentional. Judgement should be based on character, not appearance, creed, or experience. Getting laid out is a feature not a bug; if someone gets you good, use the opportunity to make a friend.”

Miller: “Hardcore the genre is fun, dumb music. What makes hardcore great is that dumb fun music can be weaponized to protect and fund your community. It can encourage growth and safety. It’s magic.”

Weston: “Hardcore is a form of expression. It’s rebellion, which is often referred to as the ‘spirit of hardcore’. It’s not one specific sound and it’s hard to define without experiencing. In a few short words, it’s positivity, love and growth through aggression and sorrow.”

Jacob Weston’s Three-Step Guide to Maybe Understanding Hardcore:

1. Go to a show

2. Listen to “What We Know” by The First Step, “Give Blood” by Bane and “Songs to Scream at the Sun” by Have Heart, focusing on the lyrics and how they make you feel

3. Read Pat Flynn’s breakdown of the Fiddlehead song “True Hardcore (II)”

Moshing to the Moon

Where does the MMHCC want Lansing hardcore to be by the end of 2025? The wish list is as follows: more venues, more people and more recognition.

Mayhem also expresses a desire for the scene to stay positive; doing good beyond providing a space for people to have a wild night.

“The variations of hardcore we know now all came from the confrontational and politically charged early hardcore punk scene. I just want more people—musicians and show-goers alike—to really think about the roots of the scene and what this should be all about. Music has such a profound influence and power that we’re not using it correctly if the content, purpose and experiences are meaningless.”

Said Smith: “Maybe Hawaii. Beach episode.”

Photos in this article are courtesy of Bret Backus. You can find more of his work on Instagram @_scumlxrd.