The Haçienda | The Legacy of Madchester

November 23, 2020

The Haçienda was a Manchester club known for its turbulent history, as well as its prominent stature in the independent music scene. Following Ian Curtis’ suicide and the dissolution of Joy Division, the band’s surviving members formed a new band, called New Order. The newly named outfit opened the Haçienda in 1982, sustaining the club through their record sales via Factory Records.

The rise of rave culture in Britain was simultaneous with the development of venues like the Haçienda as a construct of urban nightlife, with “ravers” congregating in nightclubs all across the city. The growing popularity of a new genre, “acid house,” allowed the Haçienda to become a conduit for new musical thought and experimentation. With the introduction of MDMA (a type of psychedelic “designer” drug used to extend the ability to dance) into Manchester, the Haçienda became fertile grounds for the development of “baggy/Madchester,” a new movement of psychedelia, as well as jangle pop and acid house. Despite hosting some of Manchester’s most legendary shows and an entire genre developing on its dancefloor, the Haçienda closed its doors in 1997 after nearly 15 years of innovation and non-stop raves.

The main reason why the Haçienda was so artistically successful was the free environment inspired by Factory Records and New Order’s lack of business acumen. The use of MDMA gave ravers immense energy, and the soundscapes born from the psychedelia began to nestle their way into performances. These new sonic palettes intended to mimic the effect of drugs, such as MDMA and LSD, create a spacious, slurred and repetitive production style in its breadth.

Contrasting with the slower pace of 1960s psychedelia, the proliferation of acid house led to a more bouncy feel, incorporating aspects of dance and creating what would be known as baggy or Madchester. The Haçienda became something of a silk road for Ecstasy in the rave scene. In fact, the drug became so colloquially known that the unofficial iconoclast of Madchester was the smiley logo, an image referring to the inclusivity of the scene and the “smiley” effects of Ecstasy.

Despite the obvious success of the music coming out of Manchester, Happy Mondays’ Shaun Ryder had his doubts about this new cultural movement, citing in a 1990 MTV interview, “There’s a lot of Ecstasy in this town at one time, so that’s all people came for. There’s nothing special about it.”

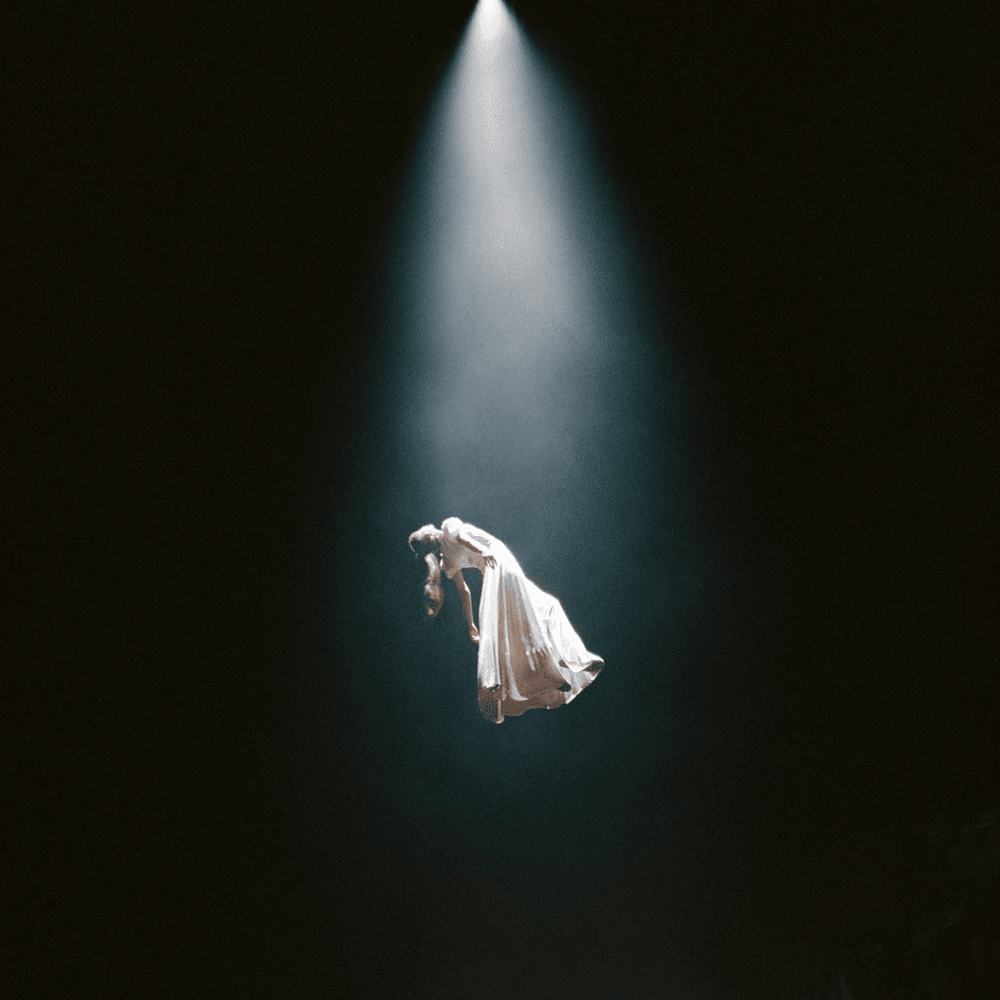

Special or not, the hedonism of the Haçienda’s dance floor was nothing but transcendent.

The participants of the Haçienda were largely young adults from the surrounding area, who would participate in shows until the early hours of the morning. Much like the Northern Soul movement of the late ‘60s being fueled by the drug “Speed” (amphetamine), the Madchester sound of the Haçienda was fueled by Ecstasy (MDMA).

Those involved with the baggy/madchester scene were usually easily identified by their mode of dress—baggy clothing and Timberland brand boots. The baggy clothes allowed for both breathability and comfort while dancing. The value of freedom was sacred among participants; while the baggy dress code allowed for comfort while dancing or tripping, it reinforced and further symbolized the hedonistic attitude of the Madchester movement.

Beyond the clothing itself, there were the vapid children of Britain clubbing until the break of dawn. Those left behind in the lower classes of “Thatcherism” were included in the Second Summer of Love. The disparities of the “greed is good” mantra of 1980s society created a discourse in the halted hamlets of England, and raves were an escape. The rave culture was barebones and inclusive; having a good time was now constructed by someone’s own desires rather than the constraints built around them. Anyone could rave, and a rave could include anyone.

The Haçienda was the lifeblood of the rave and psychedelia culture of the ‘80s in Britain—the blood that oxygenated the inhales dangling off the teeth of everyone in sight. The heart however, was hemorrhaging financially, with Peter Hook estimating that “£6m of Factory Records’ profits being sunk,” in his book The Haçienda: How Not to Run a Club. However at the heart of the shows wasn’t drugs but rather collectivism, describes Hook. When they were used, it was “only around 10% of the clientele,” and instead of some deeply spiritual time with your friends, it was used to fuel the party.

Aside from the drug statistics and his bleeding record label, Hook also reveals more social facets from his book about the Haçienda during its heyday. The venue was known for its prize wheel that was spun during shows. Each inlay featured a variety of rewards, such as “FREE BAR,” “20p OFF THE LOT” and “DOUBLES FOR THE PRICE OF SINGLES.” These prizes would further characterize the free spirit and in-the-moment mentality of rave culture and its participants.

However, the Haçienda wasn’t immediately successful. The Smiths and New Order were the only bands to have ever sold out from its opening for the first year, but the show they played together is often remembered for being “one of the best gigs in Manchester history” by its participants, and even by Peter Hook.

“Battle of the Bands” competitions would consistently highlight the new talent that was running wild in the Manchester scene. The second ever performance of a new band called Happy Mondays would instigate their rise into the limelight on Factory Records with 1985’s Forty Five EP. After their track “Hallelujah” was released, Happy Mondays would later come to the forefront of the Madchester scene, garnering critical acclaim with 1990’s Pills ‘n’ Thrills and Bellyaches.

Outside of the Manchester pop scene, the Haçienda was an important relay of new artists across the Atlantic. Artists such as Madonna and The B-52’s would perform at the venue during the club’s peak, with the former being catapulted to superstardom.

“We were once again ahead of the trends,” said Hook. “We already knew of her through association with Kamins, Jellybean, and Arthur and she had no profile in the UK at all; that appearance at the Haçienda changed it all for her.”

Beyond conventional pop and musical culture, the Haçienda became a prominent space for the LGBT community during the 1990s. Their “Flesh Night” and its controversial “no straights” policy at the door cemented the club as an important outlet for LGBT culture, attracting ravers nationwide. The culmination of these led to the Haçienda being named “Britain’s most outrageous night out,” “Best Gay Club Night of the Year” and also recognized as “another landmark night of the era,” recollects Hook in his book.

Acid house, rave, and baggy/Madchester reached their peak in 1988, sending the Haçienda into the mainstream.

“It used to be empty all the time, now it is packed every day with 8000 sweaty, happy people,” said Hook. Many of the acts that defined the sound of Madchester would go on to influence the release of the 1991 Blur album Leisure, an immensely important precursor to the development of Britpop. Acts like The Stone Roses and their self-titled debut are cited as among the “best of their generation” by NME, and according to writers Sean Sennett and Simon Groth, they had built a “template for Britpop,” proving the psychedelic innovation of Madchester was potent and immediate with its influence.

Beyond the domestic scope of its influence and the forthcoming Britpop explosion, baggy/Madchester would begin to gain international attention. Happy Mondays would prove to have international success, with their single “Kinky Afro” topping the US alternative charts in 1990, as well as “Step On” reaching #57 on the Billboard Hot 100. The Charlatans would also garner international appeal, with “Then” reaching #4 and “The Only One I Know” reaching #5 on the US modern rock charts.

The Haçienda was, in all accounts, a terrible, expensive idea from the get go. Despite the profits from New Order’s records vanishing into the exhales of a brazen youth, the social capital rivaled that of the monarchy. The venue was the stimulus for the heartbeat of the Madchester scene.

The vibrant, communal shows created this feeling of familiarity and egalitarianism among Margaret Thatcher’s divisive, capitalist system. The spacious, psychedelic textures warping off the synth-pop of the 1980s proved noxious to the populous. The MDMA-slogged shoe streaks of those clubbing created an escape where love and celebration would outshine all the parasitic tendencies of the present. The intrinsically British sound of performers created a landmark precursor of Britpop that would emanate through the pillars of the dancefloor.

A hacienda is defined quite simply as “a home,” but nobody would have ever expected it to become home to so much. Despite the rubble of the Haçienda up-drafting into the Manchester smog over some 20 years ago, the movement that the Haçienda was home to has long since abandoned its stead.