Beats Without Borders | GAS

February 3, 2020

During what could be called the “golden age of techno” throughout the 1980s and ’90s, digital composition of music flourished, especially in France, Germany and the United States. Clubs formed in major cities around the world, with blacklit basements flickering the pulse of midnight youth. Distinctive scenes were born in areas like Detroit, London, Cologne and Paris, giving rise to techno, IDM, club music and electronica. As these wildly brazen styles broke further into the mainstream, their epicenter’s cutting edge releases became a callsign for every urban basement club shaking the concrete above.

Techno had its heyday during this period, spawning variants such as minimal, ambient, Detroit and acid. Within the realm of ambient techno, there are several recognized figureheads including Aphex Twin, Biosphere, B12, The Orb and GAS, each with a distinct sound.

GAS is the most widely known moniker of German producer Wolfgang Voigt. Though not as widely known as Aphex Twin, Voigt is heavily responsible for the spread and realization of the Cologne techno scene. Founding the legendary record label Profan, Voigt himself was instrumental in the robust reputation of German electronica throughout the ‘90s and into the present.

The GAS discography starts in 1995, with Modern, released on Profan, and the self-titled release on Mille Plateaux in 1996. These records serve mostly as footnotes of the burgeoning minimal/abstract techno scene, which would later be honed into the revised GAS canon from 1997-onward.

Contrasting than the cookie-cutter minimal techno of his previous releases, Voight’s GAS project would undergo a stark transformation in 1997. The abstract and detached vapor of the previous releases was forgone for an eerily natural and cacophonous sound: the idiosyncratic whisper of wind rustled leaves with the footstepped clang of a 4/4 beat.

Voigt’s albums under the GAS moniker are meant to replicate his experimentation with LSD in the Konigsforst recreation park forest during youth. They capture the vibrancy of both the drug and the forest as a powerful dynamism of the human experience.

In 1997 Voigt released the first proper album under the sonic concept of GAS: Zauberberg.

The cover is adorned with a heavily saturated, red-scaled photo of a forest; Zauberberg is an album whose cover is indicative of the journey the album offers. The album is dark, dissonant and paradoxically industrial with its overarching tones of isolation and fear. Zauberberg offers night as a device that has scared mankind since the dawn of civilization; a haunting mass of the unknown.

This gritty and millaristic sickness slowly poisons the forest into a labyrinth of darkness. The wretched thump of the bass almost rusting the forest with its marathon; Voigt’s siren-esque strings softly blanketing the record with static pops and its distant drums. The seemingly “long night” has an anxious and abrupt rhythm to it, until the sun begins to rise from out under the shadows.

The dawning of 1999 brought a lighter and more lush record, Königsforst. Rather than a palette of unforgiving darkness, the sonics explored are more jovial and relaxed. The mellow and homogenic explosion of sound pulsates the awakening of the forest, with every heartbeat giving more and more life to the song cycle.

Voigt’s use of harps and punchier kicks allow him to illustrate a more realized soundscape illuminated by the sun on the autumn foliage. Königsforst is a passive look at the mechanical rhythm of nature and its awakening from the sleep cycle.

The restraint of morning tapers into the complex and lively teem of Pop, released in 2000. GAS’ Pop was critically acclaimed, lauded as a masterwork of electronica at the time of its release and is increasingly favourably into the present. Rather than the hue-shifted cover adorning Königsforst and Zauberberg, Pop is beautifully saturated in daylight’s angelic glow. Everything that is alive, flowing and moving as one symbiotic unit is paradoxically prominent as a separate sample. Each leaf of every tree rattles into a metastasizing jetstream of natural vibrance. The flowing rivers and streams ground the timbre of insects and birds into a wonderfully decadent and floral chimera. Pop maintains the textural captivation of Zauberberg with the sonic immersion of Königsforst, creating not only one of the landmark ambient techno albums of the modern age, but also in all of ambient music as a whole.

Many suspected that Voigt retired the moniker completely after Pop, however, after a long hiatus he returned with 2017’s Narkopop.

Narkopop serves as an alternative to Zauberberg, an antithesis of Pop and a complement to Konigsforst. The cover art is a quiet and luxurious grove in a calming blue filter. Its sonic palate maintains the tonal poignancy of Königsforst and Zauberberg as well as the expansive textural saturation of Pop.

The lush tranquility of night is explored as the duality of night to fear. Rather than the darkness of the unknown, Narkopop is a complex exploration of night’s facet of serenity. Instead of the constant presence of darkness, Narkopop is more reminiscent of the natural, objective look at night. The sun has set on the afternoon of Pop, and the moon shines on the foliage to cast a darker hue. With the eventual and inevitable end of the illumination of darkness, Narkopop’s serene and uncompromised beauty begins to transform back into Zauberberg, and Voigt has come full circle on his discography’s exploration of human emotion, setting and the cyclical cog of a mechanism that is ever-turning.

GAS presents an idea that is as wonderfully complex as it is superficially simple, and has created some of the most conceptually stunning, emotive, and enthralling ambient music that has been created.

GAS’ chronology doesn’t end with his 1997-2017 song cycle of albums – GAS’ current status ends where it begins: psychedelics. Rather than the immersion of oneself in the forest under the effects of LSD, 2018’s Rausch represents the loss of oneself. Unlike the rather disjointed structure of the other GAS albums, Rausch is meant to be consumed in a single sitting.

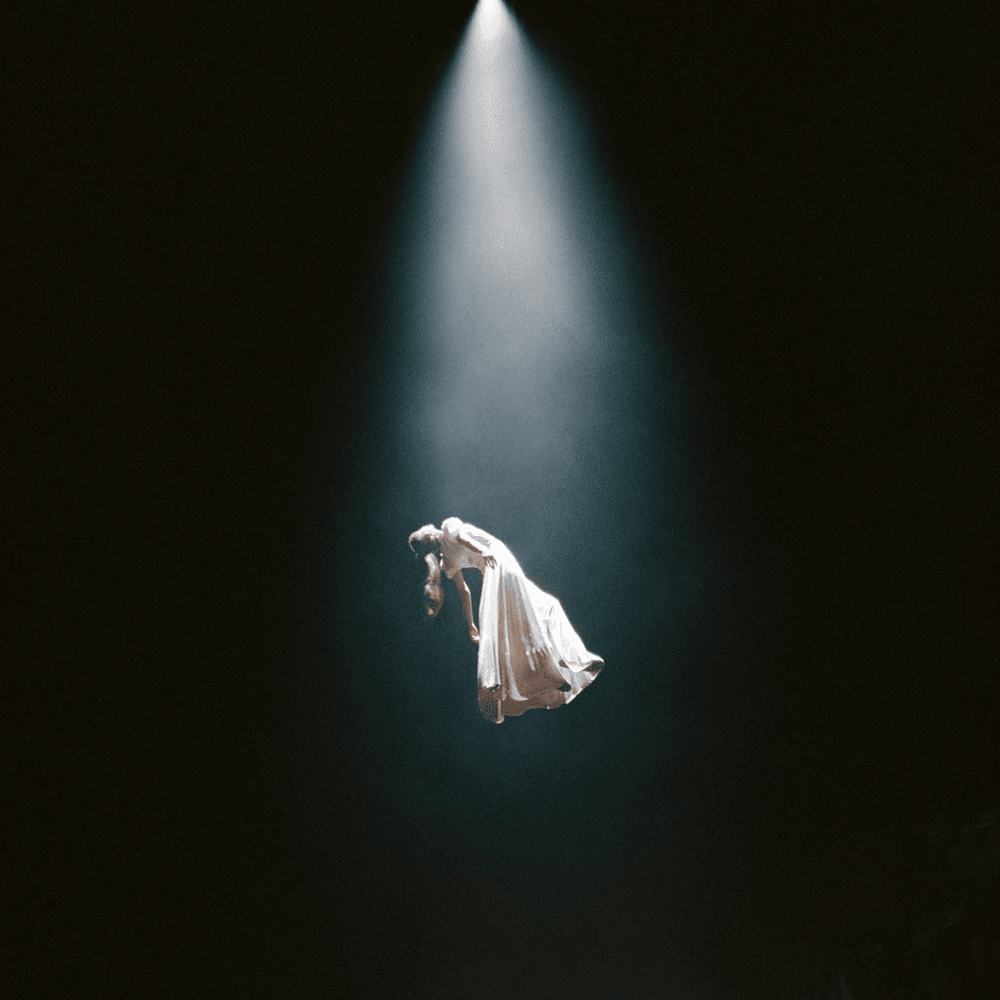

You start off feeling nothing, noticing nothing, underwhelmed by the slow burning tamber of cymbals anchoring the instrumentals structure. Yet as the album continues onward, you recognize the slow building wall of sound and the album’s 4/4 heartbeat. The intimidating whirlwind continues to consume the instrumentals and subvert the nuance of GAS’ compositions. Much akin to actual ego death, Rausch culminates into a slowly expanding sensory overload that peaks into a terrifyingly overwhelming haze that beckons your silence. It traps you in a state between consciousness and unconsciousness with its emotional stagnation. The frenzied bellow stalking the listener vanishes in its perpetual immediacy. It has consumed you. It is no longer malicious; it is everything.

The encroaching darkness washes over you in a total consumption of the ego, and you become violently ejected from the pilot as a controller of the universe. Catatonic, fractured, clueless, enlightened. The menacing kick of terror slowly evaporates into a total dissolution of detached emotion. It’s gone now.

In a bittersweet reminiscence, Rausch stripes itself of its power, slowly decaying from a textural shift of eventuality to finality. It leaves you grounded, yet aware as you regain the control you otherwise had relinquished. Nevermind what it took; you try to look onward towards its departure, but all you see is the inexplicable beauty in the wake of its rampage.

Wolfgang Voigt’s mokiner GAS is perfectly indicative and acutely self aware. GAS, much like emotion is an abstract entrapment of something that cannot be captured. We can see it, we all know it’s there – we can tell by feeling it. Voigt attempts to define those distant, wispy memories of the psychedelic ether into a coherent experience. Through his masterful manipulation of the forest around him, he creates his minimalist palate of chords, kicks and textures, Voight fulfills the emotional completion and despondency that LSD can give to its users. His mission was to “bring the forest to the disco,” but I don’t think Voigt had ever anticipated that he’d bring so much more to so many listeners.