Parting Albums: Three Artists’ Last Gifts to Music

April 20, 2019

The artist’s blessing – and curse – is to never be satisfied with what they’ve created. The drive to improve is paved with constant self-doubt. However, in the circumstance that an artist becomes aware of their impending death, what happens to this mindset?

The idea of creating and releasing an album with the knowledge it will be your last suggests an amount of confidence and self-actualization that seems to fly in the face of this idea. An individual artist has nothing to gain after the release of an album like this, so what are they trying to say? What role does the audience play in this situation?

By exploring 3 albums created in situations like this: the studio album Blackstar by David Bowie, the instrumental album Donuts by J Dilla, and the live album 98.12.28 男達の別れ by Fishmans, we can take a deeper look into what it means to create with the knowledge that you’ll no longer be able to create afterwards.

Donuts – J Dilla

J Dilla’s Donuts is an instrumental album that sounds almost incomplete, full of untraditional rhythms and samples that all come together to form a distinct piece of postmodern art. Produced during Dilla’s extended visits to the hospital, the album loops infinitely over itself (almost like a donut or something!).

When asked about the process of creating Donuts in his final interview with Alvin Blanco for Scratch Magazine, Dilla said that the collection of instrumentals on the album was “just a little compilation of stuff I thought was a little too much for MC’s.” He chose not to rap at all throughout the project and let the samples speak instead. They serve as space for Dilla to project and meditate. Songs like “One For Ghost” take an autobiographical approach and “Glazed” allows Dilla to share his thoughts on international conflict and war. In its 31-song tracklist, it seems like every song has a purpose and fills it. An album like Donuts is one man’s meditation on his career and influence, and gives the discography of J Dilla a sense of closure. The album is a cathartic and introspective reflection for James Dewitt Yancey the man, not just the producer.

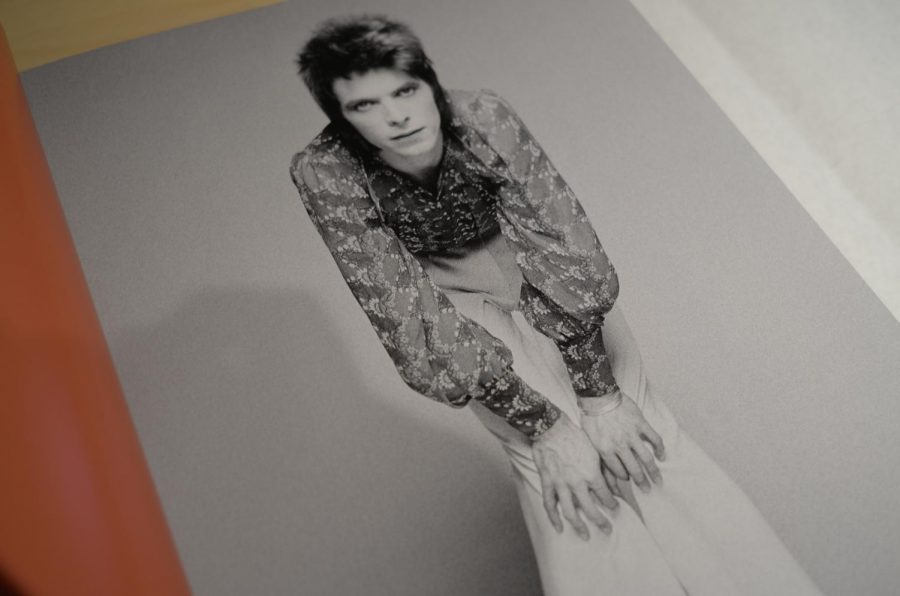

Blackstar – David Bowie

David Bowie handles the situation of his imminent death in a way that only he can. Instead of making an album as a form of individual catharsis like Dilla, Bowie made this album with a team. Coded messages, cryptic imagery and occult themes are prevalent throughout this project. At the time of its release, only Bowie himself and a few close family members knew that he was suffering from liver cancer. Between the albums release and Bowie’s death, many music publications gave the album a lukewarm reception. After his passing, however, many publications and reviewers changed their opinion. This gives the audience and public a unique role in ascribing meaning to the album. The window of time he had between release and his death shows that Bowie had no intention of making it obvious he was suffering from any illnesses.

This album was also created during a long period of media silence from Bowie. At the point of its release, he hadn’t given an interview in over a decade, nor had he sung a single note publicly since performing “Changes” with Alicia Keys at a charity event in 2006.

Sessions for the album would last up to seven hours. Drummer Mark Guiliana said in an interview with Rolling Stone: “He’d just go from 0 to 60 once we walked out of the control room and into the studio… his vocal performances were always just stunning, amazing.”

Obviously Bowie was deeply passionate about the final product. Even down to the music video for the single Lazarus, directed by Johan Renck, Bowie is seen performing his own epitaph. A final send-off to fans and family alike, Bowie made sure to make an album as complex and deep as his own career.

It seems that Dilla and Bowie both had a similar mindset in their approach to the release of their albums and how they wanted the audience to view it. The albums were made for nobody but themselves, and the audience was asked to give meaning to the different themes and abstractions presented. With no recorded lyrics, only Dilla could truly know what everything in Donuts meant. To this day, people are still creating new theories about Bowie’s Blackstar.

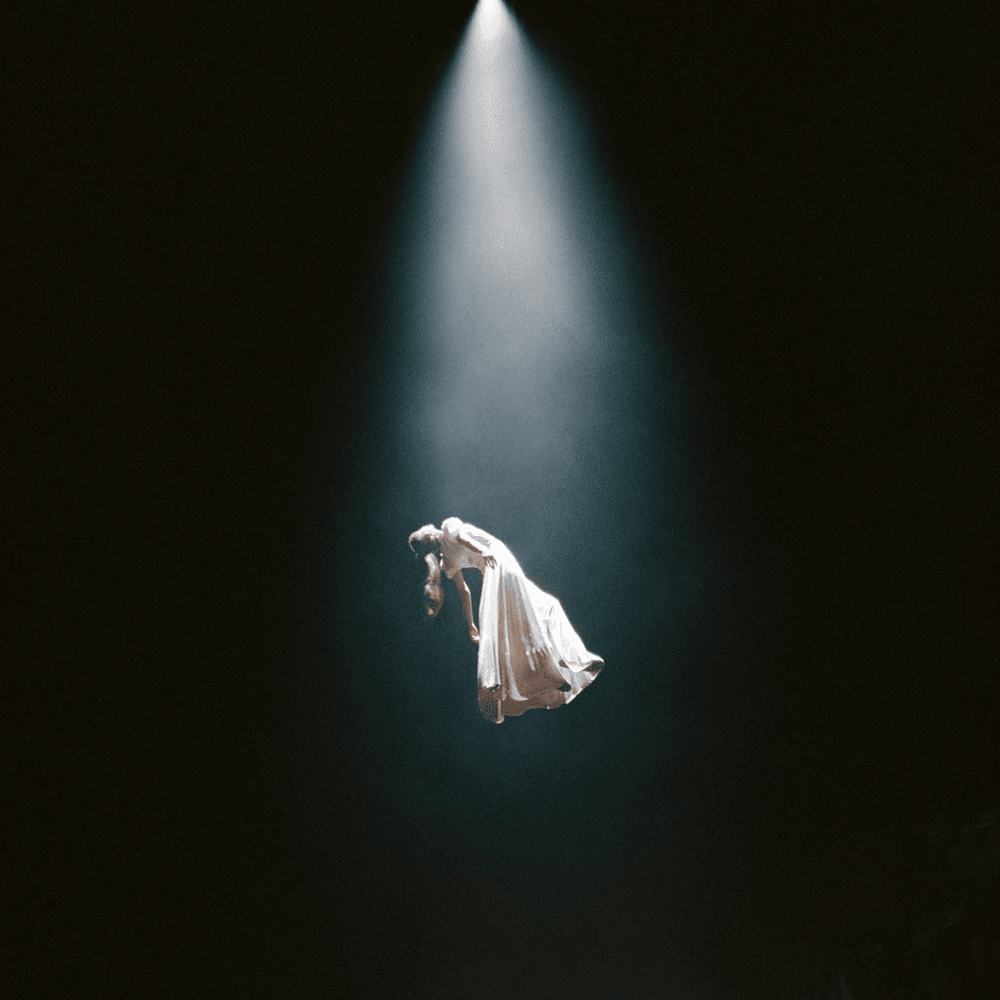

98.12.28 男達の別れ (Live) – Fishmans

The final final album on this topic is a live album titled 98.12.28 男達の別れ by the psychedelic Japanese dub band Fishmans. The title of the album roughly translates to “A Man’s Farewell: December 28th, 1998”. The man in question is the band’s bassist, Yuzuru Kashiwabara, and was meant to serve as a last hurrah for the band as a trio. Unbeknownst to everyone at the time, this was also the group’s last live appearance before the death of frontman Shinji Sato due to lifelong heart problems. The concert is just over two hours long and highlights songs from the band’s entire career.

At the time of release, the group wasn’t very well-known outside of Japan. But in the past couple years, this album has become lauded by several online music communities. Beautiful, disorienting, and melancholic, this album is one of the most otherworldly concerts you will ever listen to. Although there is a bit of a language barrier, the emotional impact is heavy throughout the entire performance. The opening song, “Oh Slime,” builds up to an incredible climax with Sato wailing his heart out. Ending with a full 35-minute live play-through of their album Long Season, this is something everyone should try to listen through at least once.

This album is unique from the others as it’s much more spontaneous and in-the-moment, like a live album should be. This seems to give way to much more emotion and passion simply because you can’t sit down and actually work on any particular piece too hard. Fishmans faced the challenge of looking back at their entire career, and creating a set that they felt would encapsulate the moment.

Not a lot of information exists in English on what the band members thought about this performance, but through this album we can see the finale of a career being given as much love as it possibly can.

Conclusion

It’s important to acknowledge that the albums I’ve chosen to try are all veteran artists far into their careers, each having developed their own unique voice. If a younger musician or group was placed in a situation like this, could they have developed something as powerful as these examples? It seems that the experience you gain over a long career of performing and recording gives you the confidence required to make a statement like the albums mentioned. Outside of music, the questions posed in this piece can apply to film, art and writing.

What are some other examples of art released in a period during the artist’s life like this? Leave your answers and general thoughts in the comments, and thank you for reading.

Feature image by Ron Frazier.