Critics love the tortured artist, and what genre is more fitting for self-criticism and contemplative anxiety than rap? While the earlier generation of rappers took the mic to express perceived issues affecting their neighborhoods and black America, more and more of the younger generation is embracing a form of rap that examines either the man behind the mic or the idea of what a rapper really is. [su_pullquote align=”left”]“…the trials and tribulations of growing up in run down projects, dodging gang violence and avoiding peer pressure all while trying to understand who Kendrick the man is.”[/su_pullquote]

Kid Cudi garnered critical acclaim by laying bare his inner demons on his two-part Man on the Moon albums. The single “Mr. Rager” became a massive hit not only for its minimalist, haunting production and creative music video, but because it directly discussed Scott Mescudi’s battle with drug addiction. Kanye West more or less built a media empire by blurring the line between person and persona, particularly on My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and Yeezus.

Kendrick Lamar seemed to be taking the same route with his critically acclaimed good kid, m.A.A.d city. Adopting a persona that, like Kanye, skirted the line between fiction and autobiography, Kendrick brought to light the trials and tribulations of growing up in run down projects, dodging gang violence and avoiding peer pressure all while trying to understand who Kendrick the man is. At that point, it was the capstone to his career. it goes beyond a character study of Lamar himself to a study on the character of hip-hop.

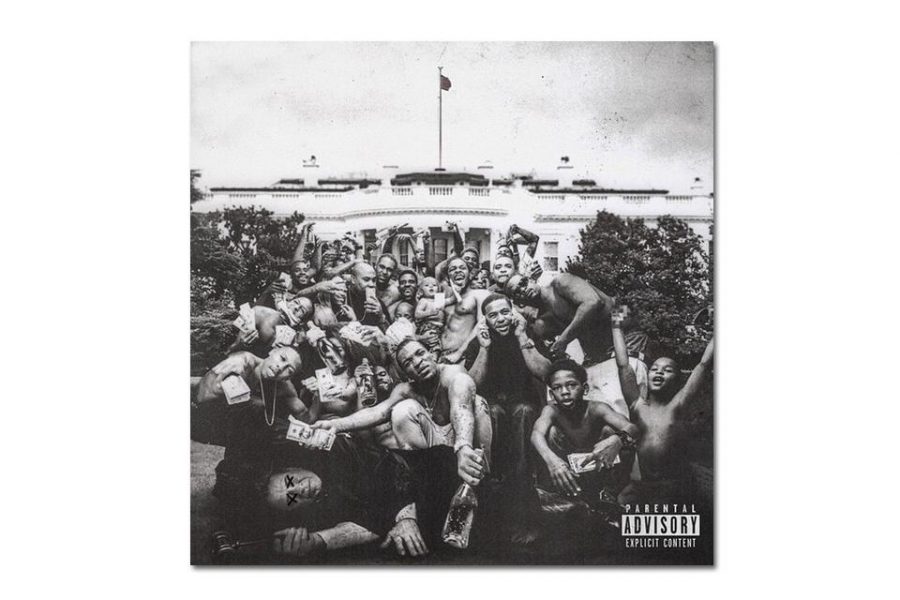

To Pimp a Butterfly is still self-reflective in a sense, taking a good portion of its 79 minute run-time to allow Lamar to directly question his influence as a rapper and his position as a black man in a racially charged America.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]”it goes beyond a character study of Lamar himself to a study on the character of hip-hop.”[/su_pullquote]Just a casual listen to the production on this album will show that Butterfly is a much more musically ambitious record than good kid. Opening track “Wesley’s Theory” grooves along a funky bass line, courtesy of Thundercat, with a psychedelic sounding distortion effect that sounds straight out of the 1970s. The following interlude track “For Free?” is a free-form jazz improvisation that is half a spoken word rant and half a tongue-in-cheek slam poem. Trip-hop extraodinaire Knxwledge lends his talents on “Momma”, creating an earthly, natural stream for Lamar to let his verses flow. “The Blacker The Berry” features the talents of producer Boi 1-dah and is a constantly tense track, with a hard-hitting boom-bap rhythm suspended by a menacing guitar feedback.

[su_pullquote align=”left”]“In an allegorical tale, Lamar undergoes the metamorphosis from a caterpillar to a butterfly.”[/su_pullquote]There has been plenty written on the all-star cast of collaborators and producers on this album-which includes Flying Lotus, funk legend George Clinton, jazz prodigy Terrance Martin and up-and-coming R&B stars Bilal and Anna Wise. While Butterfly is hardly the first rap album to draw influence from or directly sample musical styles that developed hip-hop, it structures all these different genres and sounds around a cohesive narrative to keep the listener engaged. In fact, it is the wordplay and lyricism that Lamar works with on this album that truly demonstrates his growth as an artist and storyteller.

In an allegorical tale, Lamar undergoes the metamorphosis from a caterpillar to a butterfly. In the caterpillar stage he does nothing but consume, justifying this behavior in “Wesley’s Theory”. “So you better cop everything two times/Two coupes, two chains, two c-notes/Too much ain’t enough both we know/Christmas, tell ‘em what’s on your wish list/Get it all, you deserve it Kendrick.” He is strung along by Uncle Sam, representing consumerism and material wealth, and Lucy (short for Lucifer) who is introduced on “For Free?” and expounded on later in “For Sale?” Both interlude tracks outline Kendrick’s downfall into egotism and selfishness, transitioning into the cocoon stage that makes up most of the album.

The cocoon is composed of contradictions and soul searching. “King Kunta” finds Lamar walking tall and reveling in his rise “from a peasant to a prince to a motherf*****g king.” But the pride is temporary. “These Walls” symbolizes the actual cocooning of Lamar. The walls themselves hold multiple meanings, the walls of a hotel room that Lamar is having sex in, the prison walls of a man who is the baby daddy of the woman, and later the inner walls of Kendrick’s mind as he begins to criticize his position and moral contradictions. On “u,” the counterpart track to the peppy single “i,” Lamar lets loose an incisive criticism against himself, delivering gut punch after gut punch in a delirious, drunken ramble: “You ain’t no brother, you ain’t no disciple, you ain’t no friend/A friend never leave Compton for profit or leave his best friend/Little brother, you promised you’d watch him before they shot him.”

Right after, there’s an immediate denial that comes with track “Alright” and later “Momma,” where Lamar reaffirms in a chorus (sung by Pharrell for his only production credit on the album) that “We gon’ be alright.” On “Momma,” Kendrick claims to hold an omnipotent level of knowledge about life that display a supreme arrogance. “I know everything/I know everything, know myself/I know mortality, spirituality, good and bad health/……I know everything, I know cars, clothes, hoes and money/I know loyalty, I know respect, I know those that’s ornery/I know everything, the highs to lows to groupies and junkies.”

“Hood Politics,” “How Much A Dollar Cost,” “Complexion (A Zulu Love),” and “The Blacker the Berry” details moments in which Kendrick comes to understand the issues surrounding him and the emotions that come with it. In “Hood Politics” he learns that the fight to survive contest that made up so much of his life in Compton is no different anywhere else, even at the White House: “From Compton to Congress/Set trippin’ all around/Ain’t nothin’ new but a flu of new DemoCrips and ReBloodlicans.” “How Much A Dollar Cost” sees Lamar debating with an old homeless man that “Every nickel is mines to keep” to which the old man reveals himself to be god and tells Lamar the real value of a dollar is “The price of having a spot in Heaven.” He absolves himself in the end of the song and aims to unite blacks against racism in “Complexion (A Zulu Love.)” The solidarity is undercut right after with “The Blacker The Berry” highlighting the hypocrisy of self-racialized hatred: “So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street?/When gang banging make me kill a n**** blacker than me?/Hypocrite!”)

Finally, the transformation is complete, Lamar has more or less risen as the butterfly, a complete human being that understands their purpose and direction in life. Uniquely, the single “i” has been replaced on To Pimp a Butterfly with a live recording in which Lamar stops halfway through to address an argument breaking out in the crowd, “So we ain’t got time to waste my n****. N****s gotta make time bro.” He follows up with an accapella verse in which he takes back the infamous N-word and uses it as a point of pride, “N-E-G-U-S definition: royalty; King royalty – wait listen/N-E-G-U-S description: Black emperor, King, ruler, now let me finish/The history books overlooked the word and hid it/America tried to make it a house divided/The homies don’t recognize we be using it wrong/So I’ma break it down and put my game in the song.”

The album’s closer, “Mortal Man,” finds Lamar turning his self examination and criticism on the listener directly, asking, “When sh*t hit the fan is you still a fan?” He likens himself to a prophet, wishing to be loved like Nelson Mandela and hoping that people will see him as a messenger of positive words. The last half of the song features what is probably the most profound moment for the entire album. Using clips of a 90s interview with the famed Tupac Shakur, Lamar holds a back and forth conversation until he pulls out a diatribe written by a friend of his outlining Lamar’s world. As he reads, sporadic and uplifting free-form jazz swells while Lamar illuminates the ying-yang nature of the selfish, consuming caterpillar and the enlightened butterfly. But it’s the very end when Kendrick asks, “What’s your perspective on that?” that To Pimp a Butterfly reaches its narrative climax.

There is no response from 2Pac because Lamar has presented an ultimatum that could only have existed in the present. After years of anguish and inner turmoil, Lamar has found the message of hope and empowerment that he feels the black community needs to hear right now. In a world characterized by so much increased racial tension and identity destruction, To Pimp a Butterfly immortalizes the indomitable soul of black America. Lamar has become this generation’s 2Pac with an album that is important not only in the long history of rap’s maturation but as a cultural marker of the 21st century. To Pimp a Butterfly will undoubtedly become a powerful thread in the cultural fabric of America for years to come.

To Pimp a Butterfly was released on March 16, 2015 by Top Dawg Entertainment, Aftermath Entertainment, and distributed by Interscope Records.