As Women’s History Month comes to a close, it is important to acknowledge the impacts that so many women have had on fields of music all across the world. Some of these artists help to bring entire nations together, and uplift entire continents with their music. South African singer Miriam Makeba is one of these artists.

Makeba was bestowed the nickname of Mama Africa, and yet somehow this bombastic nickname doesn’t seem to be enough for her. Her life was a turbulent one, being born in during Apartheid, escaped an abusive marriage, survived cancer, spoke against Apartheid to the United Nations, was banned from returning to South Africa, was also banned from the United States, performed at numerous independence celebrations, saw the downfall of Apartheid, and so much more. To call her a matriarch of music is an understatement.

Born in 1932 just outside of Johannesburg, Zenzile Miriam Makeba was the only child of her Xhosa father and Swazi mother. Despite the joyous time surrounding Makeba’s birth, her mother was arrested for selling umqombothi, a homemade beer, eighteen days after her birth. As her family couldn’t afford the fine, this meant that she would spend the first six months of her life in a prison. As a child, she learned how to sing in numerous languages, such as isiXhosa, Sesotho and isiZulu. She also would say later in life that she learned how to sing in English before she learned to speak the language. However, before she could spend her time focusing on music, her mother fell ill, and she took a job as a nanny for a Greek family, but they refused to pay her and accused her of theft. Fearing for her life, she returned home, and had to leave her possessions behind, and that included the only photograph of her father. At this time, she had a shotgun marriage with her partner. This marriage, though, was one that rapidly became abusive, and following an attack that nearly left Makeba dead, she found refuge in her mother’s home.

At her mother’s urging, she moved into the city proper, staying with a cousin. This would then lead her to audition for the Manhattan Brothers, where she would first make a name for herself. As a member of this band, she would tour across not just South Africa, but also across Southern Africa, with shows in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. During these travels, she would experience the effects of colonialism, such as performing for exclusively Black audiences, being barred from shops, and being forced to stay in segregated areas. Following a car crash where one of her bandmates passed because the nearby hospital refused to operate on Black people, the Manhattans put on a fundraiser show for the family of her bandmate Victor Mkize, as well as journalist Henry Nxumalo, a columnist exposing the worsening treatment of Black South Africans who was found mutilated on the streets. This fundraiser helped galvanize her against apartheid.

The anxieties of life under Apartheid were captured in one of her biggest songs as a member of the Manhattans: “Lakutshona Ilanga.” The song, which was written by one of the musicians of the Manhattan Brothers, Mackay Davashe, became a massive hit across South Africa. The lyrics tell the story of where to look if a loved one doesn’t come home and in what order. The order was as follows: the police station, the jails, and then the hospitals. The popularity of this track led to an English version, “Lovely Lies.”

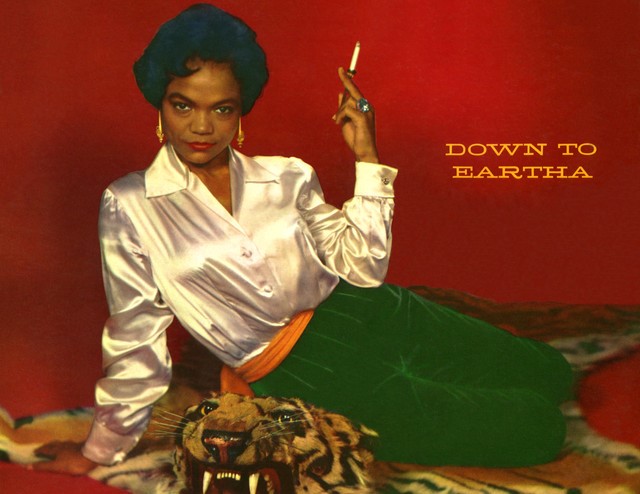

Her popularity within the Manhattans led the record company to form two other groups, the Sunbeams and the Skylarks, around her. All of the bands became quite popular across the nation, and led to her getting a chance in the first show with Black artists that performed for white audiences. This popularity across the nation gave her the opportunity to star in a documentary, Come Back Africa. The director of the documentary, Lionel Rogosin, invited her on a publicity tour. The film was a success, and introduced her to a new, European audience. This then allowed her to meet Harry Belafonte, who helped her secure her a visa to the United States. She was able to be one of the first artists to spread South African music and culture to the world, unfiltered by Apartheid. One of the songs that exemplifies this is “Qongqothwane.” A traditional Xhosa wedding song, the song is known better by the name “The Click Song,” as in Makeba’s words, “they could not pronounce “Qongqothwane.””

Makeba was on top of the world, but just as quickly, grief struck. In August of 1960, Makeba was informed at a performance in Chicago that her mother passed away. But as she attempted to return to South Africa to bury her mother, her passport was revoked, beginning her life in exile. During this time, she performed for then-President John F. Kennedy, and was quickly becoming a star in the United States. Her fame also caught the attention of those in the civil rights movement.

As decolonization spread across the world, Makeba became an unofficial ambassador of South Africa. She toured across East Africa, where she learned the song “Malaika.” This song, which was sung in Swahili, became one of her biggest hits. She would also perform in newly-independent Suriname and Tanzania. She would also be invited to perform at the inauguration of the Organization of African Unity, where she would rub shoulders with anti-colonial leaders from across the continent, ranging from leaders of then-independent nations like Algeria and Liberia to leaders like Amílcar Cabral and Kenneth Kaunda from and Guinea-Bissau/Cape Verde and Zambia respectively, and Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia amongst others. Makeba, as a voice for South Africa, also was invited to address the United Nations about conditions in South Africa under Apartheid.

With Makeba’s growing status as an activist, she would be invited to attend the independence ceremonies of many nations, including Kenya and Guyana, as well as receiving a Ghanaian passport from President Kwame Nkrumah. During a trip to Guinea, she was connected with Kwame Ture (known then as Stokely Carmichael), and the two got married soon after. Her association with Ture alienated the government of the United States, and the two moved to Guinea to avoid the near-constant surveillance from Washington D.C. During her time in Guinea, she continued to forge connections with pan-Africanist leaders, and performed across Africa. Years later, she toured with Paul Simon and Hugh Masekela for his Graceland world tour. This tour was heavily criticized by those against Apartheid, accusing Simon of breaking the UN cultural boycott, while Makeba and Masekela were accused of selling out.

When Nelson Mandela was freed from prison, Makeba fell to her knees in joy. She had been in touch with Winnie Mandela since she called to express her condolences following the passing of Bongi Makeba, Miriam’s daughter. She ended up making plans to meet up with Nelson in Stockholm, and at his request, she went to the South African embassy in Belgium to try and return. Despite a laborious ordeal, she was able to finally come home. Her return was joyous, with a humongous crowd complete with paparazzi and singing, as well as a joyful reunion with her brother Joseph. Mama Africa was finally home after 31 years. The song “Welela,” the title track off of the album of the same name, was written by her grandson, Nelson Lumuba Lee, showcased her hope for the future.

Her first album recorded in South Africa since her return was 1991’s Eyes on Tomorrow. Her album was one of hope, and her vocals carried this theme throughout the album. On April 19, 1992, Makeba had her first concert in South Africa since her exile in front of a sold out crowd at the Standard Bank Arena in Johannesburg. The crowd there was incredibly raucous, with the stomping in her song “West Wind,” shaking the whole building. Though Makeba was on tour on April 27, 1994, she was able to vote in South Africa’s first integrated elections at the United Nations headquarters in New York City. She continued performing for the rest of her life, even dying on stage in Italy.

Makeba is someone who transcends the ideas of genre limitations, and showcases what one can do with their music. Without her, African music may not have had the same esteem that it does, and it might still be incredibly difficult for African artists to break into the Western mainstream. We likely wouldn’t have hits like Tyla’s “Water,” Ayra Starr’s “Rush,” Rema’s “Calm Down,” Wizkid and Tems’ “Essence,” or Mdou Moctar’s “Funeral for Justice” if it wasn’t for Miriam Makeba triumphing over immense adversity and championing African music for new audiences.