If I were to describe Ethio-Jazz to someone unfamiliar with it, I’d liken it to bearing witness to a fragrant, home-cooked meal being shared with a friend you haven’t seen in a long time—warm, comforting, and deeply familiar. Beyond being a mere genre, Ethio-Jazz embodies a soulful and poignant spirit that merges nostalgic warmth with the raw authenticity of human emotion, crafting a beautifully layered musical tapestry.

Political instability, no matter how unsettling, has a paradoxical way of sparking extraordinary creativity, and Ethiopia’s Ethio-Jazz movement is no exception. In the 1970s, Ethiopia was under Emperor Haile Selassie’s rule until 1974, when a military council called the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC), or “the Derg,” violently seized power in a coup. The Derg implemented a brutal and authoritarian rule marked by widespread purges, forced relocations, and the infamous “Red Terror”—a campaign of political repression that led to the imprisonment, torture, and execution of tens of thousands. Along with their violent suppression of dissent, they dictated and controlled the media, including the music that could be made, produced and aired. Strict censorship rules, combined with an oppressive surveillance state, stifled creative expression and made it nearly impossible for musicians to release or distribute their work internationally. Despite these oppressive conditions, musicians like Hailu Mergia blended traditional Ethiopian sounds with Western jazz and funk, creating a genre that carried the spirit of resilience. They crafted music that not only endured but transcended its era, offering a testament to the prevailing connection between adversity and artistic creativity. Many albums, however, were suppressed or locked away in vaults for decades, isolating Ethiopian music from the world due to censorship and an underdeveloped music industry lacking the infrastructure for global distribution.

Widely regarded as the father of Ethiopian Jazz, Mulatu Astake pioneered the fusion of Latin rhythms with traditional Ethiopian melodies. While studying at London’s Trinity School, he drew inspiration from the rich musical traditions of Caribbean and West African artists he encountered, laying the foundation for his groundbreaking style. Later, studying in Boston at Berklee College of Music in 1958, he was the first African student to attend the college. During his time in the States, he was heavily immersed in the experimental American Jazz scene and studied with influential musicians such as Hugh Masekela, known for his hit song “Riot,” and Fela Kuti, a pioneer of Afrobeat. During this time, Mulatu noticed how well the five-scale notes of Ethiopian orthodox music paired with Western instruments like electric pianos and the vibraphone; thus, Ethio-jazz was born.

Due to the political turbulence the country was under, lyrics would be scrutinized for political dissent. Artists and musicians didn’t let this stop them from creating impactful music in a true display of Ethiopian resilience. Artists avoided government penalization by using specific notes, tones, and horns to replace lyrics. This subtle form of communication allowed for the conveyance of themes like resilience and identity without attracting unwanted attention. Embedded within this genre is an expression so profound that it defies the limits of language itself. The absence of lyrics shifted the attention to the music’s texture, rhythm, and mood, encouraging listeners to interpret the music on a more personal and subjective level.

What initially fascinated me about the genre was the tangible, yet abstract familiarity it brought. Producing a unique blend of sounds, scales and rhythms, Ethio-Jazz draws from multiple trends of the American Jazz scene (bebop and modal jazz) combined with melodies and harmonies based in the Ethiopian modal system. Ethio-jazz uses its unique modal system called Qañat or Qeñet, developed by the Amhara ethnic group of Ethiopia. Qañat defines the mode of a musical piece or the tuning scale of the instrument playing it. The four primary pentatonic qañat scales are Tizita (ትዝታ), Bati (ባቲ), Ambassel (አምባሳል) and Anchihoye (አንቺሆዬ). Some songs are named after their qañat, such as “Tizita,” which translates to the act of remembering or nostalgia.

The instrumentation in Ethiopian music stands out for its distinctive blend of Western and traditional elements. Western keyboard instruments are paired with traditional chordophones or string instruments, such as the masinko, a one-string fiddle similar to a violin; the begena, a harp-like instrument; and the krar, which resembles a lyre. The krar, in particular, is central to playing Tizita. Traditionally, the strings of the krar are crafted from cow gut, symbolizing the Ethiopian belief that the gut embodies emotions such as longing and nostalgia.

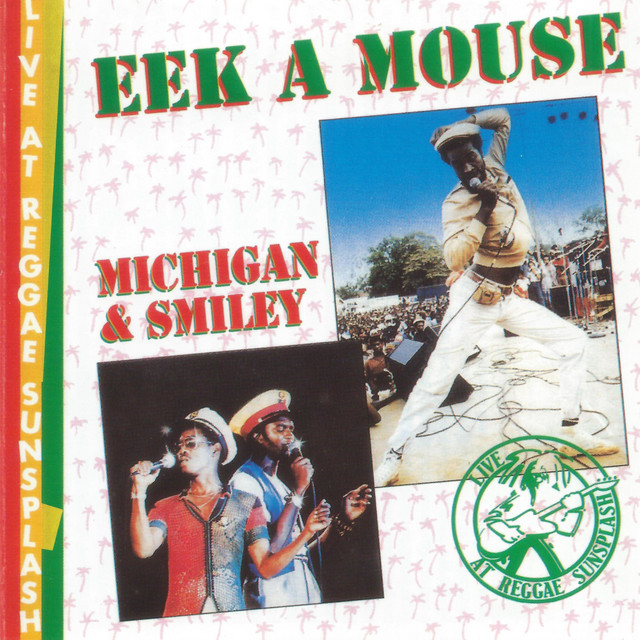

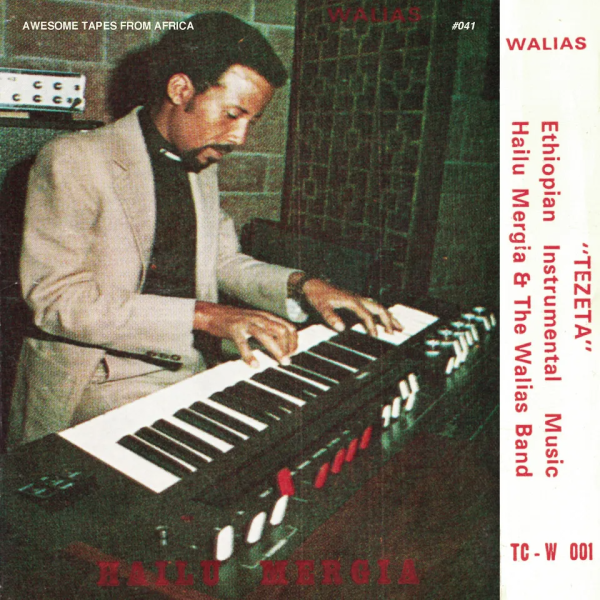

Hailu Mergia, an Ethiopian keyboardist, accordionist, and frontman of “The Walias” band, is one of Ethio-Jazz’s hidden gems from the 70s. Born in Debre Birhan, Ethiopia, a town rich in cultural heritage, his passion for music was evident from an early age. In the 1960s, Mergia moved to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, where he became a prominent figure in the city’s music scene. There, he joined “The Walias,” one of Ethiopia’s most innovative and influential bands, pioneering the fusion of traditional Ethiopian scales with Western jazz, funk, and soul influences. The band released Tche Belew in 1977, a landmark album showcasing Mergia’s keyboardist, arranger, and composer talents. Alongside Tche Belew, Mergia’s album Tezeta, also released in the 1970s, delved further into blending Ethiopian sounds with jazz and funk, further cementing his standing in the genre.

In 1978, Mergia recorded Wede Harer Guzo, an album that captured the evolving sound of Ethio-Jazz. Although initially overlooked, a new generation of listeners would later rediscover the album, contributing to Mergia’s growing influence in the genre. In the early 1980s, The Walias began touring the United States as the political climate in Ethiopia became increasingly oppressive. While most of the band returned to Ethiopia, Mergia remained in the U.S., reinventing himself as a solo artist. In 1985, he released Hailu Mergia and His Classical Instrument, an experimental album featuring accordion, Rhodes piano, and synthesizers. Despite these pioneering efforts, Mergia’s music went largely unnoticed at the time. He eventually stopped performing, working as a taxi driver in Washington, D.C., but he continued to compose and practice music in his free time.

In the early 2000s, Mergia’s music was rediscovered by global and experimental music fans. African record labels like Awesome Tapes From Africa reissued Hailu Mergia and His Classical Instrument in 2013, introducing his work to a new generation of listeners. This reissue ultimately sparked a revival in Mergia’s career, being the catalyst for touring internationally, performing at prestigious venues and festivals, and collaborating with other musicians. In 2018, he released Lala Belu, showcasing his masterful blend of Ethiopian melodies with contemporary jazz and funk elements, reaffirming his place as a living legend of the Ethio-Jazz genre. In 2020, he released Yene Mircha, further cementing his legacy as an innovator.

This article would feel disingenuous if I didn’t add my favorite albums from Mergia, Tezta, and Wede Harer Guzo. Tezta is my hands-down favorite album, and it’s the one I’ve found myself returning to time and time again. Being entirely instrumental, it embodies such a towering and triumphant sound, yet it’s not boastful nor too refined. Recorded in 1975, it’s his best album, mastering the perfect nuanced yet unpretentious sonic balance. It’s such a versatile album; there is no bad time to listen to it. Day or night, happy or sad, no matter what you’re doing, the album brings a delicate yet compelling touch of comfort, warmth, and familiarity to your day. My favorite tracks are “Tezeta,” “Atmetalegnem Woi,” “Zengadyw Derekou” and “Aya Belew Belew.” These tracks embody Ethio-Jazz: light-handed and measured yet harmonious and natural. I’ve yet to hear anything that can even come close to how this album makes me feel.

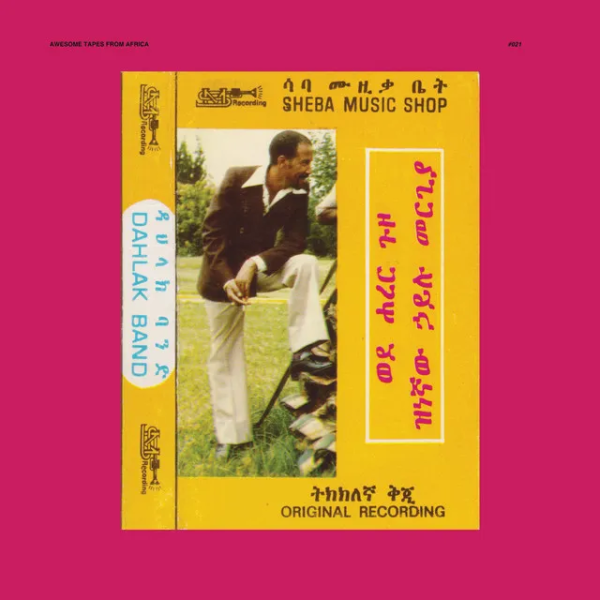

Wede Harer Guzo was the first album I ever heard from Mergia, which ultimately led me to fall in love with his entire discography and the genre. Recorded in 1978 with the Dahlak Band, translated to “Journey to Harer,” the album captures the undercurrent of the political climate in Ethiopia at the time. During the late 1970s, the Derg regime imposed strict curfews in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, which prohibited movement on the streets from midnight to 6 a.m. Amid these difficulties, musicians like Mergia and the Dahlak Band continued to perform, with clubs operating throughout the night until the curfews were lifted. The album was recorded at the club, where they practiced in the afternoons, taped across three separate recording sessions. Tracks such as “Almaz Eyasebkush” and “Sintayehu” capture this spirited, lively essence. This album retains a warm and inviting tone while embracing a more vocal and fast-paced style. Tropical undertones are remnant throughout, a nod to the band’s island heritage, rooted in the Dahlak Archipelago, a cluster of islands off the Red Sea coast near Eritrea.

Wede Harer Guzo radiates infectious energy through its rhythm, skillfully balancing bold, dynamic layers of instrumentation with tranquil harmonies. Tropical nuances ripple through every track, with an emphasis on the upbeats that add a fresh dimension to the album’s signature blend of traditional Ethiopian horns and melodies. My favorites from the album include “Anchin Kfu Ayinkash,” “Migibima Moltual,” “Almaz Eyasebkush” and “Wede Harer Guzo.” With the unified incorporation of powerful and commanding horns and light, feathery island sounds, these tracks maintain a perfect harmony between power and grace. Despite being on the more experimental end of the genre at the time, this album still retains a warm, nostalgic atmosphere.

Mergia’s contributions have undoubtedly made a profound mark on Ethio-Jazz, exemplifying the power of artistic creation in the face of adversity. The resurgence of this genre is more than a mere return to a musical tradition; it serves as a powerful reminder of the perseverance and creativity of artists who continue to forge new paths despite the odds. In spite of the political upheavals that have shaped Ethiopia’s past, the music of pioneers such as Mergia, The Walias, and the Dahlak Band resonates with modern audiences. The enduring appeal of Ethio-Jazz today reflects its profound emotional and cultural significance, echoing Ethiopia’s unyielding spirit. This revival not only honors the legacy of the genre’s founders but also underscores how music, born from passion and struggle, endures the test of time and remains culturally and artistically vital.