What have I done? Muttering to yourself frantically, you feel cold sweat run its course down your spine. Behind you is the faint rumbling of the engine still on, your car carelessly parked in the road. The soft glow of headlights pelt your back like darts as it illuminates the figure in front of you. You see it sprawled out on the cement while you ignore the heavy rain coating you in a sheet of sin. What have I done? Perhaps muttering it again will fix the problem or rejuvenate your brain. The figure lies limp and the face is obscured. With absolute certainty in your heart, you know the true identity of the figure: yourself.

With a sprawling catalog of albums – over 10 studio albums, not including the multiple live recordings and EPs – Car Seat Headrest, fronted by Will Toledo, has truly revolutionized the indie rock scene. From Bandcamp darling to headlining Coachella, a sense of authenticity, vulnerability and transparency has plagued every body of work Toledo has touched. Loosely named after Toledo’s own personal experience recording vocals alone in his 2000 Toyota Sienna (as first seen on the cover of 1), Headrest began as a hidden project from his real friends to experiment sonically. As his small community grew, so did his ambition, and eventually Headrest morphed from a one-act project into a four-piece band.

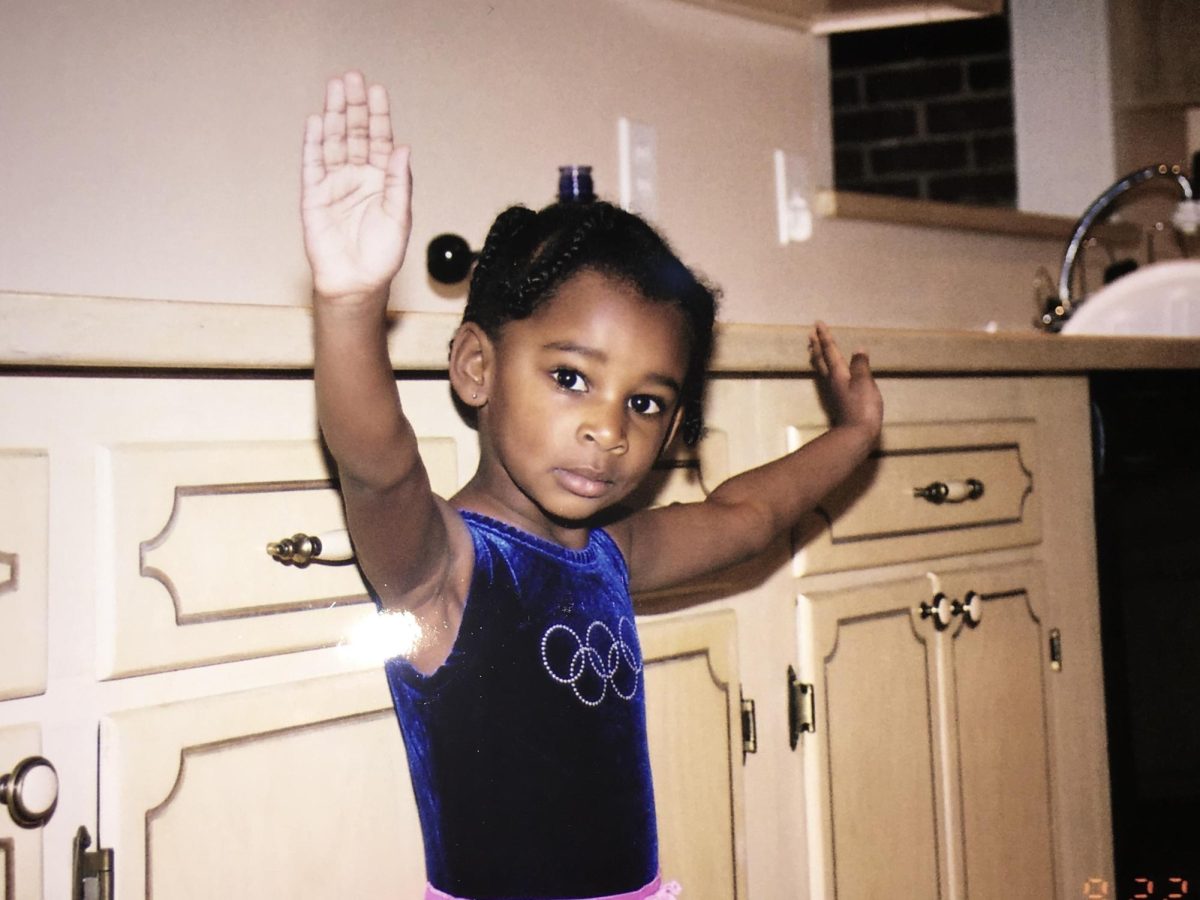

Ten years ago on Oct. 31, 2014, Headrest pushed out digitally what would be the final album to release before Toledo’s life was transformed, and quite honestly, what transformed my own. How to Leave Town is a sprawling LP (yes, at an hour and two-minutes long, it is not an EP, Mr. Toledo) that stands as the peak of Headrest’s lo-fi days. Written during Toledo’s transitional period between his short-lived college experience and the launching of his musical career, the album is riddled with witty existential doubt and a general haze of dissociation. Gloomy and dreary, this album was my first introduction to what I now call my favorite band. To celebrate its longevity, I’d like to drive down the interstate and maybe even answer the question I’m sure we’re all wondering: how do you leave town?

Spanning almost exactly five minutes, synths come in waves, blaring like sirens, over an anxiety induced breakdown that feels like forever – and I think that’s the point. A contender for one of the coolest album openers of all time, “The Ending of Dramamine” sets the tone of the album in the most blunt way possible. It’s the waiting, or the anticipation, that is often more dreadful than the main event. To what exactly is it we should be terrified of? As the song combusts into one more sporadic scream, a silence passes over, followed by Toledo’s vocals narrating a tragedy over a single synth.

“The drunk’s face breaks into sweat /

As his friend falls under the wheels /

But the headlights don’t flinch /

And the engine doesn’t stutter.”

Murder. In the blink of an eye, a person is dead, so eerily contrasted by the anthropomorphic lack of care of the vehicle lingering in the dead of night. As Toledo mourns his loss of character, describing himself as a selfish and irrational individual, as listeners we can quickly discern that this event is not a set of characters but a retelling of a true tale. No, I do not mean to imply Toledo is a criminal, rather this story is a symbolic expression of dissociation. With later lyrics that push negative attention towards others (giving the track it’s title) or state concerns with how one is perceived, I think it is clear that the “friend” who is killed by the “drunk” represent Toledo’s inability to remove the burden of past memories and attempt to, essentially, kill his past.

Toledo struggles to characterize himself through his words – something that runs its course across the entire tracklist. Greatly concerned with his efforts being “futile” and wondering what his place in “space” is – which foreshadows a moment later on the album –, Toledo ultimately resorts to describing his mental turmoil as nonsense scat. Immersed in a gorgeous breakdown with some quintessentially Headrest lyrics, “Dramamine” comes to its final words.

Toledo comes quite close to his goal – he almost escapes town! Unfortunately for him, and for anyone who has suffered with similar mental struggles, the blame game can only last so long. The eyes of the presumed dead, or the proverbial tormenting ghost of his past, follow Toledo to the edge of town and he is forced to head back to his homeland. The wrath that ensues in the monstrous breakdown of crackling amps and layers of drums implies this fight won’t be won on the first song, but might need eight more tracks to start to resemble any form of a victory.

In order for Toledo to become an adult, though, he needs to at least bury everything he once felt – simple, right? Toledo tries really hard to forget his past sins, distracting himself with a change of scenery. “You’re in Love with Me” is the most upbeat track of the album with blissfully ignorant lyrics and massive instrumental breakdowns. Layers of guitars stab sharp palm-muted melody lines while dissonant chords slowly build up to a crescendo. This buildup allows for the mellow tension exhaled on the last track to come back to an emotional foundation – Toledo’s determination to wipe his mind clean and drive further down the road. In traditional Headrest design, the romanticization of another is lost in a cloudy haze that leaves one to question how much of it is real and how much of it is just an escape from reality.

“You could be in love with anyone /

But you’re not in love with anyone /

Because you’re in love with me.”

On first listen, it sounds like Toledo is approaching a happier state in his life, leaving behind any mental baggage and rejoicing with a lover. On a closer examination, though, Toledo implies a level of disconnection that continues to run rampant in his life. The lover could be in love with anyone (aren’t we all anyone?), but they aren’t – they’re in love with our narrator. By disconnecting himself from “anyone,” Toledo subtly implies having the inability to resonate with the rest of society. Its wordplay is reminiscent of the classic tale of Odysseus and Polyphemus in “The Odyssey,” where our protagonist similarly embodies a pronoun entirely when christening himself as “nobody.” This admiration of another person yet recognition of the distance between two people starts to lay the groundwork of the toxicity Toledo faces on the coming tracks.

Toledo recalls a strange dream in the form of one of the funniest Headrest lyrics, further revealing our protagonist’s self-centered nature when he struggles to enjoy even the company of his own subconscious’ creations. With the chorus coming back again, we continue to question how this relationship will unfold. Our narrator is incapable of appreciating himself before attaching himself to outward sources of happiness. As the song concludes on a final breakdown with his repetitive insistence that his lover is in love, we are reminded of a similar characterization in “Sober to Death,” where Toledo slowly loses his hold on what once brought him comfort. Desperate and unstable, Toledo must find some hope soon before all hell breaks loose.

Fantasy seems to be the easiest way to indulge in our hopes and dreams. Opening with an acoustic yearning of the distance one must travel, “America (Never Been)” feels like the blueprint to Toledo’s titular question. With witty remarks, we learn of the great distance spanning America, most likely representative of the great length one’s journey to seek individuality really is. Toledo likes to imagine a scenario where he has changed so much he floats like a ghost through the places he once occupied, finally arriving down the path he wants to go – it’s reminiscent of something Bob Dylan would write.

After apologizing to the ocean during his lonely traversing of the interstate, Toledo gets close to self-awareness when battling an internal angel and devil. He recognizes the constant questioning of his own character is no healthy way to live, yet he continues to drive out of a desperation to learn. It’s a twist of the typical American virtues (it’s the land of the free!) to help represent his own lack of control, eager to find his place socially and artistically. He’s living in a land of grand opportunity, yet is stuck at the bottom of the mountain, looking up at the overwhelming height he must climb to reach any sort of freedom. This hopelessness is compounded when the chorus comes with powerful distorted chords and repetitious decrees. Toledo references his own experience reading a biography on Franz Kafka, stopping his experience short when he reaches the time Kafka was writing a novel titled Amerika. Similar to the dissociation from the present on the previous track, Toledo, in a meta fashion, implies how we often prematurely miss out on our dreams (the alleged American experience) when we live out the actual typical American life.

“All my fantasies are faking orgasms /

They’re only in it for the money I made up for them /

I trade in ideas, opinions and artistry /

And my face is on every dollar.”

These dreams conceived on the journey across the country are really only there for selfish reasons: to try and relieve Toledo of the aches of true hardships. By the end of the song, Toledo is starting to sound pretty annoyed by his lack of relief he thought he’d find. As the motif of his inability to connect with another person when struggling to enjoy himself is further pushed, layers of harmonies and screeches ring out a satirical chant of what America really isn’t. As Toledo continues to transition into adulthood, he becomes concerned that there really isn’t a perfect place for him to exist. With a lonely little synth to round out the track, we’re left with a sense of alienation, wondering how exactly we can categorize our hopelessness into the right places to see change come to fruition.

All of the unspoken words come gushing out as Toledo nears the end of his roadtrip on “I Want You to Know That I’m Awake/i Hope That You’re Asleep.” There’s a bluntness typically restrained in order to poetically posit emotions here as Toledo somberly spells out the end of his relationship with a lover. With a declaration that the monster of a beast that is the concept of love has utterly baffled Toledo, dead memories ran over earlier in the album are brought back to life. The past experiences one has lived, or the previous mental health struggles one has faced, often come to bite the foundation of a relationship – communication – at its core. With a stuttering of words, the struggle to articulate turns sour when an attempt to communicate is ultimately abandoned all together.

“Here is a demo of my last sentence /

I’ll fill in the good parts later /

I’ll make it fit together real nice /

And cut out all the ‘likes.’”

Massive drums fill the frame of the verses while moody, crunchy guitars capture the essence of Toledo’s reservations. His inability to vocalize his emotions throughout the album is cleverly tied up in an idealized scenario of acting as an omnipotent entity who can carefully cut and paste thoughts into words. A distance between the two characters of the song continues to build with puncturing guitars panning between ears, shooting darts with bitter remarks. As the song continues to detail the relationship’s collapse – little arguments over the smallest of things and a continued attempt at escaping by driving –, Toledo starts to direct his attention towards his place in life in the present rather than relishing in the past he killed.

Pulling in references to his heroes and inspirations – from the Beach Boys to the Beatles – he recognizes to fall from grace just as he does on “Kimochi Warui,” Toledo seems to accept the collapse of what he has built when, ironically, trying to deny it. As more denials are affirmed, the percussion builds to a loud release and unrestrained screams are belted, evocative of the unbearable weight of social impotence Toledo writes of. It’s a total scream-into-my-pillow moment that Headrest is so good at depicting, threading the line between fantastical poetry and reality when discussing an experience of naivety we often like to forget. The song never ends with a final confirmation of the presumed death of the relationship, but it really has no need to – the point of the song isn’t the relationship, but one’s own internal struggles manifested into physical, tangible entities in the form of another human being. Toledo has struggled on the duration of the tracklist to ground himself physically, and with the end of this song, it becomes clear that there isn’t a singular thing that could fix all of Toledo’s problems at once.

A need to ground oneself in reality has finally been discovered, and now we can turn our attention towards the rest of the world. Serving as a much needed interlude between two powerhouse songs, “is this dust really from the Titanic?” is the penultimate track for How to Leave Town, monologuing about the process of creating art and living as an artist on top of a simple guitar melody. Waning between the good and the bad of artistry, Toledo starts to cement himself as something worth recognizing. Although he is the furthest from a lavish life, a sense of community in seeing fellow artists around him experiencing similar lives reassures him to continue to live. As Toledo continues down the interstate, he seems to finally reach his destination – but the question still remains: has he really escaped town?

“It is 2014 and I have no idea what is going on in my life!”

Ten years later, it’s 2024 and I also have no idea what’s going on in my life. As the finale of the album, “Hey, Space Cadet (Beast Monster Thing In Space)” sees Toledo reckon with his situation with a clarity he has lacked on the earlier tracks. After an opening explosion of guitars, a mellow single guitar melody is picked with sparse percussion lingering in the background. Reminiscing over his memories on the road and grieving the distance from which he came, we start to wonder if leaving town was ever what Toledo really needed. There’s a loneliness that never escaped him on his drive – it’s an obsession with what once was through nostalgic recollection that never really leaves.

“Hey, space cadet /

You can’t hang out with your friends /

Even when you are with them.”

In a climatic summarization of the album’s themes, Toledo christens himself as a “space cadet” – a way to depict his feeling of isolation from what he’d consider “normal” to be. This is further explained in the above lyric, where Toledo struggles to understand himself and others even when physically grounded by those in his surroundings. Does it mean that the people he is with are emotionally distant and toxic for him, or is he the one who is so caught up in the inner machinations of his mind that he is incapable of existing in the present? I think this lyric is just ambiguous enough for it to really lean either way, especially when Toledo comes to a revelation that the highs of relationships he has been chasing the entirety of the tracklist are incapable of providing the kind of self-reassurance he needs to learn to embrace. He calls back to “Beast Monster Thing” when reprising the rampant love motif, now understanding that his preconceptions of how two people should interact cannot be built on a foundation of uncertainty and anxiety that creates an unsustainable notion of “love.”

What I love most about this track is Toledo’s intentional omission of his new life, or, his refusal to answer whether or not he really did manage to escape town. After being thrown all around the backseat of the emotional road trip this album is like a piece of luggage, we might be inclined to expect an answer from our narrator. The reality is a little less grand, but easier to implement than we think: love yourself, god dammit! Toledo spends so much time on the album chasing the past, drunkenly condemning his youthful mistakes and wallowing in the pity of his own mental affrays that he forgets not just how to leave town but why he desires to in the first place. The keys to everything we yearn for, whether it be a stable relationship or the ability to create powerful art, are always with us. It’s not cruel or narcissistic to be able to set our foot down on the pedal and say “I’m going where I want to go simply because I want to” – in fact, it’s the best way we can hold out hope against the unwanted voice in our head that demands to swerve down a different road.

With a minute of careful instrumental buildup climaxing into a gut-wrenching guitar solo, we are left alone with our thoughts to consider why we might want to leave town as well. As the final words of the album reassert Toledo’s admittance of his own character as one who is of value and is capable of change, it becomes painfully obvious that the man drunkenly hit at the beginning of the album is truly a manifestation of himself he has spent over an hour running from – it’s the space cadet. Even Toledo seemed to recognize this truth in the opening track, but continued to soul-search for answers. In a twist of storytelling, Toledo suggests that the journey of life is not comparable to a trip across the interstate, but more closely resembles a rocket ship launching you into space – into the unknown with little certainty that you’ll find your eventual footing. To face our fears and to face adulthood fully, Toledo declares we should hold onto ourselves and not get lost in easy self-criticism that inhibits us from living and loving to the fullest. Get out of the car, get off of the interstate, I mean, really, get out of the mean town that’s your head! We’ve got to be ready for whatever life throws at us, knowing we have the self-confidence to ground ourselves – after all, “It’s time to show them what you can do / What can you do, man, what can you do?”