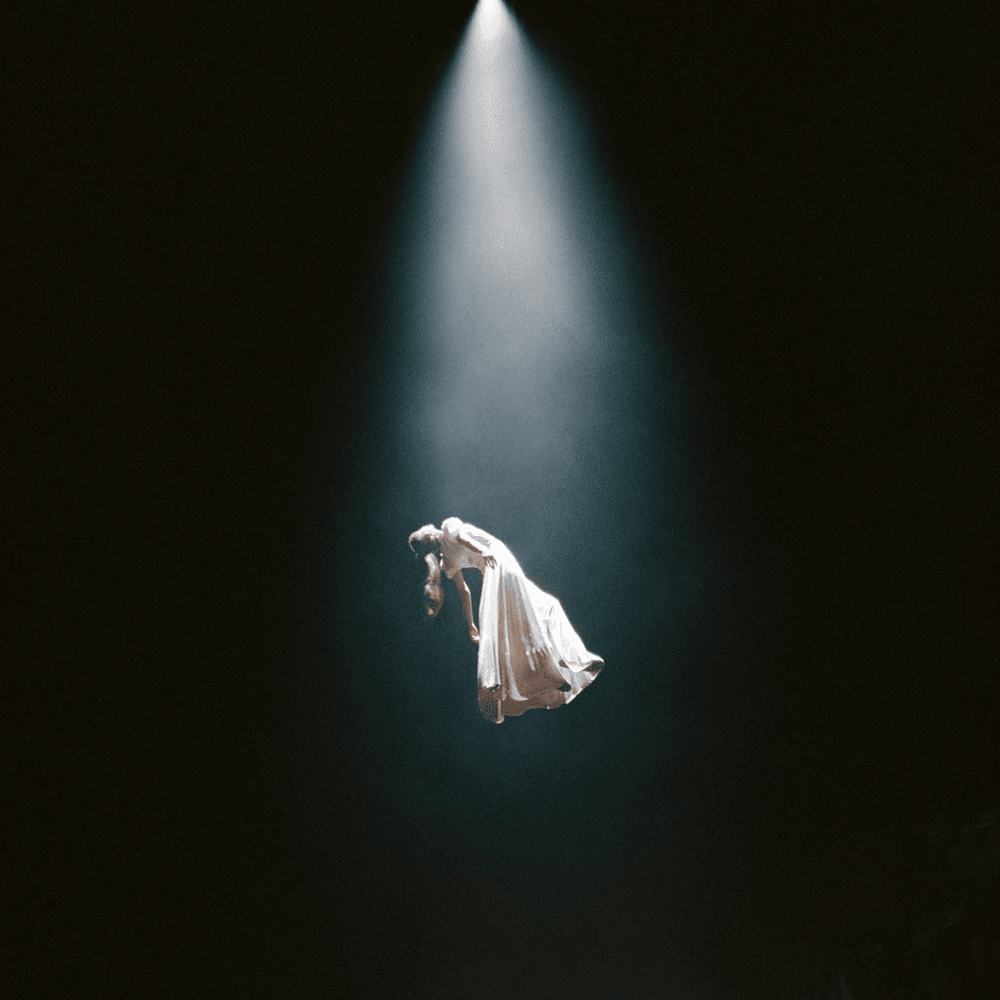

It is hard to talk about Joni Mitchell without mentioning Blue. The album, now widely acclaimed as one of the greatest of all time, has left such a legacy that it often overshadows the rest of her catalog. Blue, however, is just one album in one of the greatest discographies of all time. Beginning with 1970’s Ladies of the Canyon and ending with 1979’s Mingus, the 1970s brought about possibly the best streak of albums an artist has ever released.

One of the highest points in this eight-album streak comes in Court and Spark, her sixth studio album released 50 years ago on Jan. 17, 1974. The album reached No. 2 on the Billboard 200, a peak only matched by her live album Miles of Aisles released the same year.

Court and Spark is not only a commercial highpoint for Mitchell but an artistic one as well. It is the centerpiece of her discography and a blend of all the genres and ideas she had been working on up to that point and would further perfect on later albums — the folksier vocal inflections of Clouds, the jazz influences of Hejira and the emotional resonance of Blue. All of these elements combine with a perfect pop sensibility, a testament to her musical genius.

The title track opens the record on a softer note and sets the scene for what is to come. With a reference to People’s Park and the final proclamation of the song — an inability to “let go of L.A.” — Mitchell places the listener in the California of 1974. She has “sacrificed [her] blues” and is welcoming love back into her life. Though the track seems like a relatively familiar piano ballad from Mitchell at first glance, the hints of pop rattling underneath the surface feel incredibly distinct to this era.

“Help Me” continues this theme of welcoming love back into her life. She’s falling again, and she’s falling fast. Through this, however, there’s still a hint of anxiety as both she and her lover are “flirting around” and “hurting too.” Charting at No. 7 on the Billboard Hot 100, the song became the biggest hit of Mitchell’s career. Its ear-worm chorus and breezy instrumentals were made with mass audiences in mind, but it does not sacrifice Mitchell’s songwriting genius and attention to detail.

“You dance with the lady /

With the hole in her stocking /

Didn’t it feel good?”

“Free Man in Paris” takes on the perspective of David Geffen, the president of Mitchell’s former label, Asylum Records. It’s a tale of a trip to Paris, away from all of the phone calls, business deals and “star-maker machinery.” The track became yet another hit for Mitchell, peaking at No. 22 on the Hot 100. It is one of the most feel-good moments within her discography — nothing but pure joy as she glides through the track feeling “unfettered and alive.”

No one can depict a scene quite like Mitchell. “People’s Parties” sees her take on an all-knowing perspective of several partygoers. She seems to see directly through these people as she describes their “passport smiles” and “cutting” personalities. This perspective does not come without some introspection, however. She can see through herself just as she sees through others — her lack of humor and her “frightened silence.” The track unravels as Mitchell moves inwards, recognizing her own weaknesses and becoming a little too self-aware of the performance she is putting on for others. As the song begins fading out, she begins “laughing it all away,” a longing to not take everything so seriously. As brilliant as it is poignant, “People’s Parties” is the perfect showing of Mitchell’s lyrical genius.

“I’m just living on nerves and feelings /

With a weak and a lazy mind /

And coming to people’s parties /

Fumbling deaf, dumb, and blind.”

Mitchell takes a more spiritual tone on “The Same Situation,” connecting religious allusions to her seemingly never-ending search for love. Even throughout this quest she remains fully aware of her faults, her “struggle for higher achievements” and her willingness to be vulnerable with lovers who refuse to reciprocate. She turns to higher powers, calling out for “someone strong and somewhat sincere,” though she admits she’s not sure where these prayers will go. It is an acknowledgement of how many others pray for the same things without ever receiving them and that her situation may not be any different. Flowing directly from “People’s Parties,” it is every bit as wise as the previous song. It is brutally honest and in-the-moment, proven by the clear desperation in her voice as she “call[s] out to be released.”

“Still, I sent up my prayer /

Wondering where it had to go /

With heaven full of astronauts /

And the Lord on death row.”

“Car on a Hill” comes as one of the record’s jazziest tracks. Depicting a night up waiting for her lover to return — or, as Mitchell puts it, for her “sugar to show” — the track winds between fast-paced vocal sections and more drawn-out instrumental bits. This shifting instrumental is almost suspenseful, perfectly setting the tone for this emotional night. A standout feature of the track, however, is the background vocals: the more formed repetitions of verse lyrics, the muttering of “climbing” throughout the chorus and the stunning vocal riffs over the instrumental sections. It is a perfectly arranged track, placing the listener right into Mitchell’s position waiting for that car to pull up.

The sonic and emotional climax of the record comes on “Down to You,” the sprawling seventh track that won Mitchell the Grammy for Best Arrangement Accompanying Vocalist(s). “Everything comes and goes,” the track’s opening sentiment, could be seen as a thesis statement for what follows — an acceptance of the choices one makes and everything that life throws at them in return. Focalizing this acceptance through the events of a short-lived fling, she paints the scene from the moment the narrator goes “down to the pick-up station craving warmth and beauty,” until the morning after’s realization that “love is gone.” The joy leaves as quick as it comes. This emptiness is only emphasized by the two minutes of instrumental which follow that proclamation of a faded love. The track furthers the arc of Mitchell’s search for love, caught in the never-ending cycle in which “pleasure moves on too early and trouble leaves too slow.”

“In the morning there are lovers in the street, they look so high /

You brush against a stranger and you both apologize /

Old friends seem indifferent, you must have brought that on /

Old bonds have broken down, love is gone.”

“Just Like This Train” places the listener right in Mitchell’s head, both present and reflective as she darts between spectating her surroundings and working through her “jealous loving.” The airy instrumental and vocal delivery on the track work as a perfect background as she depicts the scene around her. Images like a “thin man smoking a fat cigar” or an “old man sleeping on his bags” are particularly mundane but feel worthwhile when Mitchell voices them. This imagery is interspersed with thoughts about her inability to find her goodness and a fear that she has lost her heart. It is not all bad though, as you can practically see the smile on her face as she sings about the pleasure she’ll feel watching the hairline of her “vain darling” recede.

The joy Mitchell seems to be experiencing performing these tracks is felt no more than on “Raised on Robbery.” Released as the album’s first single, the track is the most straightforward rock track she had released up to that point. It is humorous and extremely fun, as Mitchell takes on the persona of a sex worker picking up a lonely man “sitting in the lounge of the Empire Hotel.” He isn’t “bad looking,” and she isn’t “asking for no full-length mink” — a perfect match for the night. It’s a perfect tribute to the rock songs Mitchell was raised on, designed to be screamed at the top of one’s lungs.

Returning to more serious topics, “Trouble Child” leans into mental health and a pressure to conform. Mitchell is sympathetic as she describes someone aware of their faults yet unwilling to change. Alone in the world, unable to be talked to, feeling inhuman, they’re a “peacock” who is “afraid to parade.” The slightly jazzy instrumental and instantly memorable hook as she sings the titular phrase work towards the album’s greater pop sensibility while still making Mitchell a standout from her peers. As the record’s final original track, it hits many of the sonic and lyrical themes that are quintessentially Court and Spark while still pushing the record further.

“So why does it come as such a shock /

To know you really have no one? /

Only a river of changing faces /

Looking for an ocean.”

A cover of Annie Ross’ “Twisted” closes out the record, serving almost as an encore. Carrying the themes of mental health from the previous track, “Twisted” takes a more comedic twist on psychoanalysis. An analyst tells her she’s “right out of her head” and would even “be better dead,” unable to see that she is truly a genius. Though it is clearly a cover, it comedically speaks to Mitchell’s overlooked genius — an artist who was head and shoulders above her peers but didn’t see the same recognition at the time. It is the perfect closer to the record, a lighthearted nod to the jazzy style she would push further on subsequent releases.

Though Mitchell is the clear star here, her collaborators prove to be just as important. David Crosby and Graham Nash lend background vocals on “Free Man in Paris,” Cheech & Chong can be heard on “Twisted” and Robbie Robertson plays on “Raised on Robbery.” The most important collaborators, however, are Tom Scott’s The L.A. Express. The members not only added their own flair to the record but also became an integral part of her live shows throughout the following year. Their inclusion on the record signaled that Mitchell’s sound was rapidly changing — no longer just hinting at jazz but actively fusing it into her work.

The record saw Mitchell at the top of her game, achieving hit singles and critical successes while still remaining true to herself. This success, however, drew her towards more experimental and challenging work instead of sticking to the formula she had found success with. The following album, The Hissing of Summer Lawns, was seen as a betrayal to many fans who had appreciated the accessibility of Court and Spark. Just a few years later she pushed song lengths to over sixteen minutes — “Paprika Plains” — and swapped out The L.A. Express for members of the Weather Report. These advancements may have been shocking to listeners throughout the late 70s, but 50 years later, Court and Spark reads as the catalyst for the experimentation Mitchell would push herself towards on later records.

Court and Spark is a masterful blend of the genres and sounds she had touched on throughout the 1970s, all wrapped up with a pop sensibility that still remains honest and fresh. Though Blue is seen as Mitchell’s essential record today, Court and Spark is an excellent jumping off point for those interested in her work. Whether it is the rowdy joy of “Raised on Robbery” or the intimate beauty of “Down to You,” the record is filled with tracks exemplary of Mitchell’s brilliance. It is the work of an artist just reaching the peak of their creative potential — the centerpiece of one of the greatest catalogs in music.