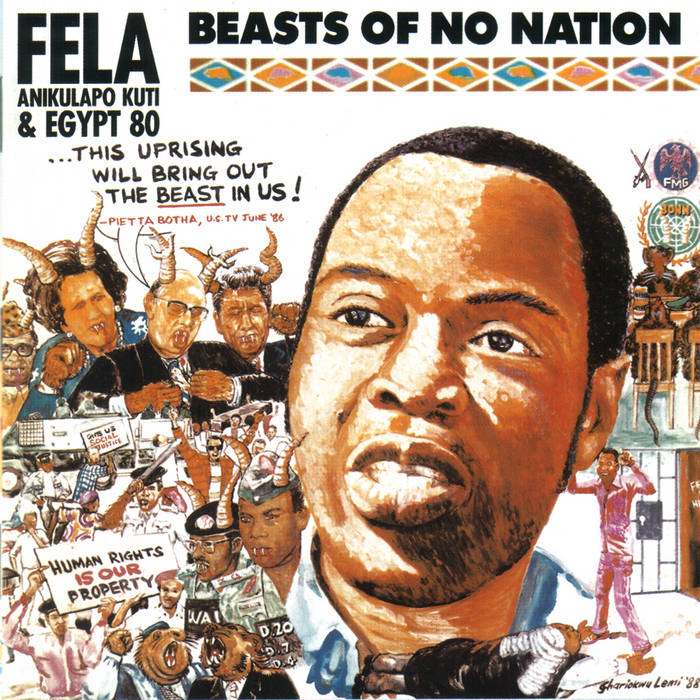

Inspired by his study of jazz, funk and Ghanaian highlife music, Fela Kuti created afrobeat music in the ‘70s. Born in Nigeria, Kuti impressed strength and moxie upon his fellow citizens. His mother, Funmilayo Kuti, was a prominent political activist who undoubtedly inspired him greatly. As a man, he was both charismatic and noble. His vibrance resonated in the souls of those lucky to have heard him.

The Nigerian police constantly harassed Kuti. His government deemed him a threat to national security. He wrote the song “Zombie” about soldiers who mindlessly follow orders and carry out heinous harassment of the Nigerian people. In response to this call out, the Nigerian army placed 1,000 soldiers surrounding the Kalakuta Republic, his home in Lagos. The siege of Kalakuta left his mother mortally wounded. An analysis of “Sorrow, Tears, and Blood” reveals the chaotic nature of the attack on his home. In addition, Kuti comments on the larger chaos that was so regular across Africa:

“So policeman go slap your face /

You no go talk /

Army man go whip your yansh /

You go they look like donkey /

Rhodesia they do them own /

Our leaders they yab for nothing /

South Africa they do them own.”

Kuti was famous for using his personal experience to speak to a larger audience. Encompassing the magic of music, he would perform nightly shows in Lagos that often ran for hours on end. The end of each song was not met with applause, but with raised fists and triumphant cries. These shows took place in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, some of Kuti’s most active years. Despite numerous jailings during this time, he was regarded as a formidable force. Even though crowds were small, he loomed large as his voice roared with anger.

Kuti was a staunch anti-colonialist. He believed that Eurocentric teachings in African schools were distorting or erasing the living culture of his home continent. Music was a way of fighting against this that he built his life around. Many of his songs are conscious of social patterns that were established by Europeans, especially those that discouraged African traditions. The music itself is a sermon that preaches Pan-Africanism, an idea that all people of African descent are united by common struggle.

Having produced over 40 studio albums in just over 20 years, Kuti’s legacy remains inspirational. Hip hop artists like Burna Boy continue to play afrobeats — the hip hop adaptation of afrobeat — on a global stage. Kuti’s impact on the world was unmistakable. He allowed improvisational funk to shatter convention and sang lyrics with chic sensitivity. He was a philosopher that rivaled oppression.