“Rumble” is the only instrumental track ever banned from U.S. radio. Officials feared that the track would incite riots, that it would bring about broken glass and drawn knives, that it would give the youth a flame with which to burn down cities.

Thankfully, things have changed, right? This isn’t 1958: Surely, our modern age wouldn’t be rife with calls to ban music, books, movies and other media — we are more enlightened now. We don’t blacklist people for giving their voice to the oppressed. We’ve learned from the Red Scare. We’ve learned from the aughts and their hysteric, xenophobic post-9/11 waves. How could we possibly make the same mistakes again?

Link Wray, the central mind behind “Rumble,” saw these mistakes pile up for his entire life. Wray, the son of a Shawnee mother, was forced to hide from the Ku Klux Klan in his younger years, and his family lived in a constant state of financial hardship. As Wray put it, “Elvis, he grew up white-man poor. I was growing up Shawnee poor.”

Wray lived with vocal and hearing issues, but his guitar spoke with greater fervor than most gifted orators ever could. It spoke to everyone who had ever taken a suckerpunch — whether literal, economic or social — and yanked them up from the bloodied ground. In each strum, there was a reason for the listener to jump back on their feet. In each distorted wobble, there was a reason to fight back.

Again, why was “Rumble” banned? The title alone was an instigator, claimed officials. But beyond the title, anyone could hear the rebellion in this instrumental. To the domineers of 1950s America, the sound of rebellion was a sound that needed to be silenced. And it seems that the sound of rebellion remains such a target today.

In 2023, Native American protestors are charged for protesting oil pipelines. Women are denied basic healthcare rights. LGBTQ+ books are stolen from libraries. Histories of the oppressed are barred from school curriculums. Employees lose their jobs after voicing support for Palestine.

Much has changed since the studio version of “Rumble” released in 1958, but still, much needs to change. Whirling between blood-soaked lines in the 21st century’s often-terrifying soundscape, the sounds of rebellion still hold a place. At times, they need to force their own place.

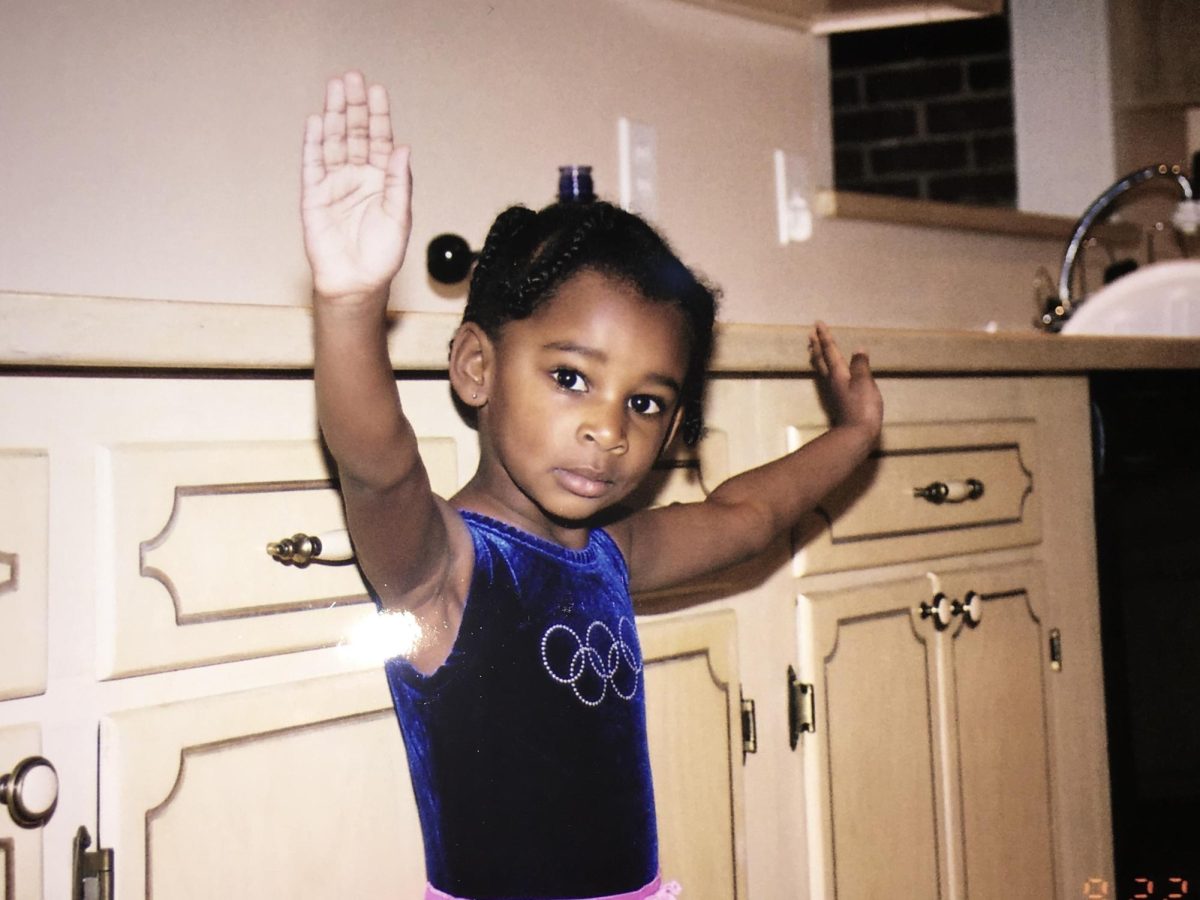

The oppressed spoke loudly in the 1950s, and only then could they find some semblance of peace. The oppressed speak just as loudly now, and they deserve that same peace. Open your ears and hear them — truly hear them. They speak through images, songs, films, essays. At times, they speak simply by staying alive.

In the spirit of “Rumble” and all it represents, hear them.