We Watch It For The Music | The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie

April 1, 2022

At the center of it all — it all being life — one must wonder what it means to be a Goofy Goober. One must put an end to that wonder by finding the truth. Is being a Goofy Goober a step closer to the divine or some form of enlightenment, or is it nothing but a vehicle of distraction from the often unbearable weight of life? The SpongeBobian philosophers of our age are in disagreement, and this humble writer is no closer to the answer. So it is fair, perhaps essential, to examine what the great minds of the past have said on the question of the Goofy Goober and those topics surrounding it. Perhaps answers can be found in that medium that so often touches the soul or its equivalent in ways indescribable to the human mind: music.

If we were to ask some past philosophical greats like Albert Camus, Socrates, Lao Tzu or Jean-Paul Sartre what philosophical threads they see in The SpongeBob Squarepants Movie, what would they say? Well, they would likely say “What the hell is The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie?” A fair question indeed. The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie is a classic example of the hero’s journey, a term popularized by literature professor Joseph Campbell which recognizes the template of stories in which a hero goes on an adventure, faces great crises, overcomes them and returns transformed.

In this hero’s journey, or monomyth, there are numerous parallels to another product of this template: Homer’s Odyssey. In The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie, we find a crew — SpongeBob and Patrick — far off from their homeland just as Odysseus and his men are far from Ithaca. We find an angry sea god — Neptune — who is present in Odyssey as Poseidon. We find a bag of wind that Princess Mindy gives SpongeBob and Patrick, just as Aeolus gave Odysseus. We find a terrifying cyclops — the scuba diver — who captures SpongeBob and Patrick just as Odyssey’s Polyphemus captured Odysseus and his men. We find David Hasselhoff, who brings SpongeBob and Patrick home to Bikini Bottom just as the seafaring Phaeacians brought Odysseus home to Ithaca. Most importantly we find “The Goofy Goober Song” whose dangerous allure matches that of Odyssey’s song of the sirens.

The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie’s director, Stephen Hillenburg, set up the movie to adapt the same literary crisis as Homer’s Odyssey. This crisis is man vs. supernatural or man vs. God, which one might be inclined to call sponge vs. God. One could argue that Odyssey contains an analysis of man vs. self as well, but The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie examines this literary crisis to a much greater extent. One might call this crisis sponge vs. Bob.

These crises are brought into greater focus through the music of The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie, as are the philosophical elements of absurdism and the Ship of Theseus thought experiment. It is ultimately “The Goofy Goober Song” which sews these threads together, but it is important to cover some of the other songs throughout the movie before and after. “The Goofy Goober Song” serves as the meat of this essay, and one could say it serves as the lettuce, onions, tomatoes, cheese, pickles, ketchup and mustard of it as well. The two buns holding this Krabby Patty of an essay together are enjoyable, but ultimately do not poke at the core of the many SpongeBobian philosophies at hand here. Now, I should admit that I am but a simple admirer of the SpongeBobian and far from a master, but this does not discourage me from commenting. As a wise sponge once said: “You don’t need a license to drive a sandwich.”

As it had to, The SpongeBob Squarepants Movie opens with a rendition of the show’s classic theme song. It is sung by a group of pirates who discover a chest containing tickets to the very movie they appear in. As they sing the theme, they sail to a movie theater to experience what they couldn’t have guessed would be so life changing and monumental. They knew they would laugh, but how could they have known that they would also cry, cheer and fall into an ocean of deep, abyssal contemplation? How could any of us have known?

After the theme song, the movie continues with a dream sequence, a vision into the subconscious or perhaps the spongeconscious — what the official term for this uncontrolled dreamland of a sea sponge is, I do not know. It seems Sigmund Freud and his students neglected to comment on matters such as these. But in this sequence we see SpongeBob’s first thoughts on meaning. We see what he associates with purpose and fulfillment, perhaps what he thinks makes life worth living. In this scene there are grandiose visions of the sponge himself as manager of the Krusty Krab 2 — a position he so greatly desires — saving the day by skillfully placing a slice of cheese on a customer’s Krabby Patty. In the heat of the action, a slick, crime-film-inspired score provides the musical backing.

SpongeBob is cool under pressure, as if he’s been preparing for this moment his whole life. Perhaps he has been. To be manager of the Krusty Krab 2 — is it to be fulfilled? Is it to be truly happy? From this snapshot, one might think so, but there is an interesting turn in the scene. SpongeBob asks the customer, Phil, if he has a family. Phil responds “I’ve got a wife and two beautiful children,” and SpongeBob says “That’s what it’s all about.” So does SpongeBob also desire to be a family man? Throughout the series leading up to this movie, SpongeBob shows no desire for romantic love. He makes no mention of a desire for a partner or a family life, but here he may be inferring something contrary to all that came before. Does SpongeBob seek romantic love after all? Does he seek a family of his own?

According to the UCMP Berkeley article “Porifera: Life History and Ecology” sponges reproduce both by sexual and asexual means, but those that reproduce sexually do not do so out of any romantic attraction to another sponge. Perhaps animated sponges act differently. Perhaps they do have a great desire for the touch of another — as would be evidenced by the existence of his mother and father and their cohabitation. But when analyzing the rest of the movie, SpongeBob does not exert any attitudes similar to those that could be interpreted from the “That’s what it’s all about” line. It is Patrick Star who seems to fall victim to love’s great magnitude, as he becomes infatuated with King Neptune’s daughter, Princess Mindy, calling her “hot” on multiple occasions.

While an interesting talking point, it does not seem that SpongeBob’s sex drive or familial desires are key to his philosophy of life, as they may not truly exist as more than a tiny bubble in his mind. But when looking at his desire to be manager of the Krusty Krab 2, it can be understood that this is the mortal receptacle in which he places meaning. And herein lies the issue for our lovable sponge: he places meaning in the transient. He seems to believe that the universe itself prescribes meaning for everyone in it, which, according to the philosophical perspective of absurdism, is certain to become a problem.

Soon after SpongeBob’s dream, that problem does indeed present itself. But what is absurdism, and how does it relate to SpongeBob’s placement of meaning in being manager of the Krusty Krab 2? An Oxford University Press article explains absurdism’s most prominent figurehead, Albert Camus, defined the absurd as “the futility of a search for meaning in an incomprehensible universe, devoid of God, or meaning.” The article also points out his belief that “Absurdism arises out of the tension between our desire for order, meaning and happiness and, on the other hand, the indifferent natural universe’s refusal to provide that.”

One might point out that a god exists in The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie — that god being King Neptune — and that the hand of one of the show’s creators appears throughout the television series. Certainly, the SpongeBobian view of absurdism may be altered by these existences but it does not seem that King Neptune or The Creator provide any form of spiritual or intellectual enlightenment that may bring about any true meaning.

There is no afterlife implied by these figures, and if we were to revisit the series once more, we would find that the episode “SB-129” does not imply the existence of God but the absence of it. Perhaps the most famous scene from the episode, the “alone” scene, supports the prospect of an utterly meaningless universe and it capitalizes on the angst that Squidward Tentacles faces in light of this direct contact with the Absurd. The absurd is made concrete here, in that it is strange and elusive, but Squidward has little understanding of the absurd at this point in the show so he faces confusion, crisis and true fear.

This scene has been used by YouTuber and SpongeBobian Philosopher Karsten Runquist to demonstrate SpongeBob SquarePants’ supposed exploration of existential nihilism, a philosophical perspective in which — similar to absurdism — the universe is perceived as inherently meaningless and without purpose. French Playwright and Philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre summed up the view of an existential nihilist when he said, “Strut, fret and delude ourselves as we may, our lives are of no significance. It is futile to seek or affirm meaning where none can be found.”

It is fair to say that absurdism and existential nihilism are quite similar. They both recognize the meaninglessness of the universe, of which we are all a part, rendering all of us conscious beings ultimately meaningless as well. They both reject the idea of hope in an afterlife, as there is no God or equivalent to God present in either philosophy. But where the divide truly lies is in absurdism’s belief in revolt. As Albert Camus stated in absurdism’s most notable text, The Myth of Sisyphus, the reasonable response to an existence devoid of a common meaning is not suicide or giving into that meaningless. One must confront the absurd head on, though it may be a meaningless task like everything else. One must seek to find their own unbound meaning since one is not provided for them. And though one’s created meaning still remains truly meaningless, Camus believed that “The struggle itself … is enough to fill a man’s heart.” So it is in this that I find The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie observable through the lens of the absurd: This confrontation of the meaningless is one that results in great joy.

Side note: It should be understood that the author of this essay paid much thought to this distinction between existential nihilism and absurdism, and went through many, many methods to determine which view would be appropriate for his analysis into The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie. Family and friends can attest to the fact that he sat alone on many nights, staring at the moon, listening to Avril Lavigne’s rendition of the SpongeBob SquarePants Theme over and over and over again until he’d finally come inside around 3:00 or 4:00 a.m. and write something down in his notebook. The mornings after, he could be found printing out pictures of SpongeBob’s house, on which he would sometimes write “The house has been burning.” One day he printed out one last picture and wrote “The house has been burning for so, so long.” Then he wrote “absurdism” on a sticky note and began to type on his laptop. One would think he would have been writing about The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie but he had turned to poetry first. It seems the combination of Avril Lavigne and SpongeBob had the man “in his feelings” as one might say. This was the product:

“Somewhere in here and nowhere else, she said something /

And we were on the river — on a rock — watching the fish, the weeds, the clay, silt and sand /

Running along it was a wall of billboards: ‘ARE YOU A SLUG?’ they all asked /

She gave me a quiet laugh. ‘God, I hope not’ /

That laugh shot me dead in between the cracks of a nearby bridge /

I was watching us there on the rock /

Watching myself say nothing /

Watching myself die under the weight of her eyes /

Watching some shining mist leak from the deep, deep /

I don’t remember the color of those eyes. I truly don’t /

‘ARE YOU A SLUG?’ I do not know /

And one day in a self-imposed winter I passed by the rock again. We still sat there /

She was cold by my fault and I was scared. I was lost in the river /

Lost in a random streak of green-orange light, selfishly warm /

I do not know why she was with me. Perhaps she was also lost in the green-orange /

Perhaps she simply enjoyed cold morning air and when the river was darkest /

She would not be sitting there for me /

But as I watched us from the bridge I called, I called, I called, I called, I did not /

I ignored her and me, then thought ‘What if I had gray hair?’ /

For a few minutes I felt less heavy.”

When asked why he wasn’t writing about The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie, the author fervently laid out how the poem was actually directly related to the movie and certainly not about anything else. To quote him: “The fish thing in line one, that’s all the fish in The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie. And the slug lines are about SpongeBob’s pet slug Gary.”

When informed that Gary is actually a snail, he responded with “Slug is an artsy way to say snail.” When told that this was also an incorrect belief, he doubled down, repeatedly saying “Slug is an artsy way to say snail,” until his doubters were simply uncomfortable. Friends and family did not care to hear about any of his other justifications on how the poem was related to The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie, so they left him alone in hopes that he would eventually produce SpongeBob-related content. End of side note.

It seems that I may have spent a little too much time away from the music of The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie. Well, I like music. I’d say I’m a fan of the medium. I wouldn’t mind talking about it a little more. Before we reach more of the movie’s musical offerings, we follow our Homeric hero SpongeBob SquarePants as he wakes up and arrives at the grand opening of the Krusty Krab 2, where his whole world comes crashing down. SpongeBob is in hell.

Yes, SpongeBob is in hell. Philosophical hell. He has met the absurd and failed to understand it. He has been told by his boss, Mr. Krabs, that he will not be the manager of the Krusty Krab 2. He has been told that the very thing that gives him meaning in life is being handed to Squidward Q. Tentacles instead. So SpongeBob is bound by the fearsome ropes of hopelessness, and there is little light that now reaches the ocean floor. His purpose in life was to be manager of the Krusty Krab 2 and now that this purpose has been erased, what is life to this sponge but suffering?

On the edge of this suffering is the Goofy Goober. And behind the Goofy Goober is its siren-like song. In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus binds himself and resists the temptation of the sirens’ sweet song, but some of his crew throw themselves off their ship, meeting their demise under the spell of a sweet, sweet lie. SpongeBob becomes both a crewmate and Odysseus in The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie, but he acts as crewmate first.

After truly meeting the uncaring face of our universe for the first time, our broken sponge is found crying at the bar of Goofy Goober’s, while the mascot representing Goofy Goober’s tangible peanut body — which surely does not exist, as Goofy Goober is such a strong spiritual force that its power could not take on a physical form, such as how one might view an almighty, all-knowing deity — sings the “The Goofy Goober Song” to a room of smiling children. The song echoes and echoes and echoes throughout the night and the lovable peanut’s endless chanting does nothing but remind SpongeBob that he is now a shell of himself. This world is a cruel one, SpongeBob. Oh how the children laugh and sing as you bury your tears in the cold, cold wood of the bar. And how the absurdity of the world follows through with Patrick congratulating you on the job you didn’t receive. Cruel, yes, but ultimately meaningless, random and uncatered.

But then the random nature of the world shines on SpongeBob in the form of ice cream. He drowns his sorrows in bowl after bowl of Triple Gooberberry Sunrises, drunkenly hollering, “Waiter! Oh waiter!” deep into the night. Who can blame the fellow? Yes, there is some kind of happiness found in this cloud of forgetting, but he has given into the siren’s song. He wakes up shitfaced as one might say, all at the hand of the Goofy Goober and its dangerous allure. But, again, who can blame the fellow?

As SpongeBob and Patrick recover and stumble, hungover, into a great quest to retrieve King Neptune’s crown from Shell City, they find themselves on a quest to prove they are men. Perhaps this is SpongeBob’s revolt against the absurd. He will show King Neptune, Mr. Krabs and the uncaring universe that he is a man. In this struggle, he will smile. But SpongeBob walks a fine line: If he understands this as the meaning of life, he will suffer. If he sees it as a meaningless pursuit that will bring happiness, he will find peace.

SpongeBob and Patrick reaffirm their status as men as they stop for gas before traveling into the SpongeBobian equivalent of Odyssey’s underworld. In this scene, the two workers who act as SpongeBob and Patrick’s equivalent to the blind prophet Tiresias laugh at them and slap their knees to some majestic banjo work. But SpongeBob and Patrick are not discouraged: “We are not kids. We are men.” says the Bob himself. Here the literary crisis man vs. self truly begins. One could say man vs. society is also applicable, but it is less important from the absurdist’s view. SpongeBob and Patrick are stuck in internal conflicts of whether or not they are men and whether or not they can prove this to society and, more importantly, themselves.

After having their car stolen less than 15 seconds after crossing over the county line, SpongeBob and Patrick end up at the Thug Tug, where one of the The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie’s greatest questions arises: How the hell did the producers get Motörhead to make a song exclusively for the movie? “You Better Swim” is a parody of their song “You Better Run.” It has alternate lyrics relating to the ocean and to SpongeBob and plays through the Thug Tug bar as SpongeBob and Patrick try to find the keys for their stolen Krabby Patty car.

“You Better Swim” rumbles throughout the joint until the most musically significant moment in the movie abruptly enters the fray. SpongeBob and Patrick — those absolute fiends — are blowing bubbles in the Thug Tug bathroom until a booming voice shouts, “Hey! Who blew this bubble?” and the fish throughout the bar collectively recite, “All bubble blowing babies will be beaten senseless by all the patrons of the bar.” Now SpongeBob and Patrick must prove their manhood by resisting the sirens’ song.

“The Goofy Goober Song” blasts through booming speakers as the bar’s patrons form a great line. There is much at stake for our dear friends Mr. SquarePants and Mr. Star: If they manage not to sing along, they come closer to proving that they are men and they escape the prospect of having bruises up and down their squishy figures. If they fail, they might fucking die.

This death would not only be a physical one, it would be a philosophical one as well. SpongeBob and Patrick would reach the belief that they are still nothing but children and their lives’ new meaning would likely be shattered. At this point in the movie, I do not believe SpongeBob and Patrick have a full understanding of the absurd, so they likely still believe that this pursuit of manhood is the meaning of life. If they found themselves to be children, their spirits would be broken. Their internal conflicts would be inflamed by the Thug Tug’s physical condemnation of their nature. The literary crisis of man vs. self would unfold into self-imposed sentencing of SpongeBob and Patrick’s character.

But it is here where I, the author, realize my stupidity, my blindness, my ignorance. How could I have discounted the literary crisis man vs. society so greatly? I have placed importance on man vs. God and man vs. self, but the dynamic between SpongeBob and the society around him is much more evident, much more substantive. Man vs. self is born of man vs. society in so many situations throughout The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie and man vs. God/man vs. supernatural is more of an extension of man vs. society for most of the movie.

It is society which puts SpongeBob and Patrick to the test. It is society which asks the two to be men. It is society which asks our heroes to conform or break. So society, which has asked SpongeBob to be a man in order to become manager, in order to earn respect from the King of the Sea, in order to live in general acceptance, now asks him to avoid the warmth of childhood and his true self. “Do not sing along to ‘The Goofy Goober Song,’” says the world. And in what I now view as a moment of pure heartbreak, SpongeBob and Patrick do not sing along. They are suffering. Once again, they are in hell. Oh, the sirens are loud and they are beautiful.

“Oh, I’m a goofy goober, yeah! /

You’re a goofy goober, yeah! /

We’re all goofy goobers, yeah! /

Goofy, goofy, goober, goober, yeah!”

SpongeBob and Patrick are crumbling. Tears break loose from their eyes. They must sing.

“I’m a goofy goober, yeah! /

You’re a goofy goober, yeah! /

We’re all goofy goobers, yeah! /

Goofy, goofy, goober, goober, yeah!”

The sins of the ocean weigh greatly on your shoulders, SpongeBob and Patrick. It is not your fault.

“I’m a goofy goober, yeah! /

You’re a goofy goober, yeah! /

We’re all goofy goobers, yeah! /

Goofy, goofy, goober, goober, yeah!”

Just as SpongeBob and Patrick are about to break loose into song, a double-headed fish exclaims “Goofy goofy goober goobers yeah!” It is saving grace for SpongeBob and Patrick, but tragedy for society as a whole. The fish is beaten senseless in the bar, and what for?

I am sorry, dear reader, but I simply cannot write any further. I will leave many strings loose in my doing so, but I simply cannot muster up the will. Though SpongeBob and Patrick escaped the sirens’ song just as Odysseus did, I cannot help but feel a great hole in my heart. I will admit there are two more things in this movie that give me hope: David Hasselhoff and “Goofy Goober Rock,” but I know it is not enough.

Ultimately, the movie ends in triumph and SpongeBob defies the philosophical thought experiment of The Ship of Theseus, as there are so many moving parts in his story and character that one simply cannot understand if he has changed completely or not at all. But I have seen this sponge bend until almost breaking. I cannot help but be saddened beyond comprehension. And I hadn’t even mentioned the song “Now That We’re Men,” which I can only see through a gray lense now. I see society’s crushing weight in the form of a cheery tune. I see empowerment achieved only through a mustache. I see the disposal of Goofy Goober underwear. I see darkness and little else.

Now that I think about it, the mariachi scene where all the fish come back to life and assault the cyclops/scuba diver does bring a little light back into the frame, but I am still in distress. Perhaps I have met the absurd once more and am now unable to look it in the face.

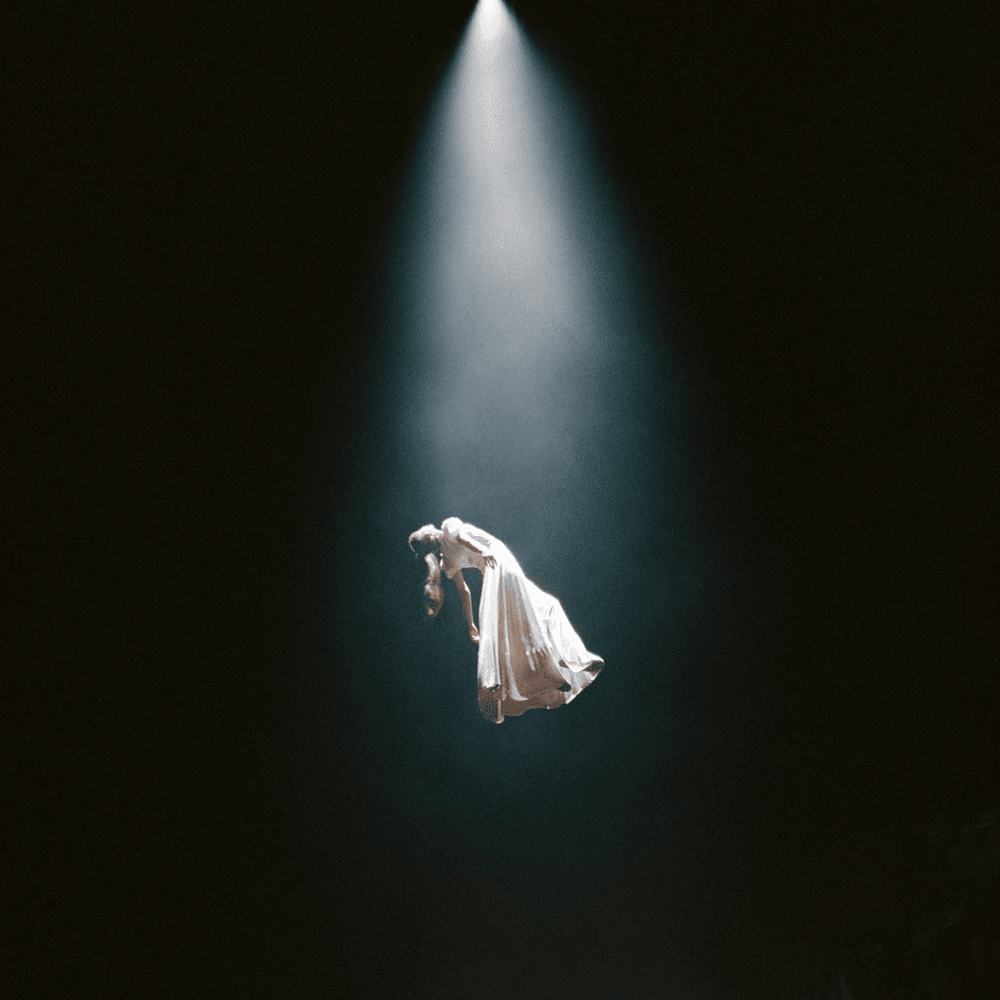

While the existence of the Goofy Goober and its shackle-breaking rock music may bring a message of hope in the face of a meaningless world and cruel society, I still cannot help but shed a tear. The absurdist view is one that denies hope in something greater, so what hope is there, really? Dear reader, in this moment — this cruel, cruel moment — this image is me.

A sponge can only absorb so much: What is tougher to absorb, some hidden greater meaning or no meaning at all? After rewatching The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie and dissecting the Goofy Goober’s many intricacies and interactions with society, I thought a meaningless world was a happy one, but is that still so as I type these words? Again, dear reader, this image is me.

Perhaps it is best to sing along to “The Goofy Goober Song” and imagine I am riding on the back of David Hasselhoff into some clouded land of nothingness. Alas, I am afraid that may not be possible. Yet as I write, I realize that is all I want. Perhaps there is meaning in the world after all. That meaning can be found while on the back of The Hoff, absorbing sea spray and looking out on a beautiful, uncaring sky. Sadly, that is not possible. Please, universe, this is all I want. Absurdism, existentialism, literary crises, The Ship of Theseus — none of it matters. Hoffism is what I have found in my writing of this. An impossible happiness, surely. A perspective I will never be able to find but in theory. SpongeBob, oh SpongeBob, why have you forsaken me?

Hold on a minute, I completely forgot that Ween’s “Ocean Man” plays as soon as the credits begin to roll. That’s fucking awesome. I think I’m feeling just fine now.