Impact Highlights: Black Artists of Modern Ambient

February 18, 2022

The story of ambient music is one that can be traced to early 1900s composer Erik Satie, who had a vision for music that served as a background rather than the center of attention. In these past 100-plus years — as ambient has passed through many, many hands to become a diverse, limitless universe of crawling sound — that vision has remained largely intact. But during its genesis, ambient has bred many subgenres and accepted numerous soundscapes to build a body equally commonplace and foreign. From the same cloud of artists one can receive a semblance of gentle wind, creeping waves or a reverb-soaked wall completely impalpable, completely unreachable by everything except some unknown part of us that catches these sounds and drives them directly into the heart. Though there are many variations in modern ambient and its subgenres — such as drone — this great web holds one principle at its center. As Brian Eno stated in the liner notes of his 1978 album Ambient 1: Music for Airports, “It must be as ignorable as it is interesting.”

Ambient has its legends like Brian Eno and Erik Satie, but the variation and growth the genre has experienced in the past century wouldn’t have been possible without less-heralded Black artists such as King Tubby of the 1970s Jamaican dub scene or Brian Eno collaborator Laraaji. On the path to ambient as it is known in the 21st century, these were key figures in the progression of the genre. In the current ambient scene, Black artists continue to shape what is possible. With their unique arrangements of field recordings, samples, synths, classical instrumentation and much more, artists KMRU, Klein, Ibukun Sunday and Dedekind Cut have each been welcome contributors to the scene and are essential to highlight individually.

KMRU

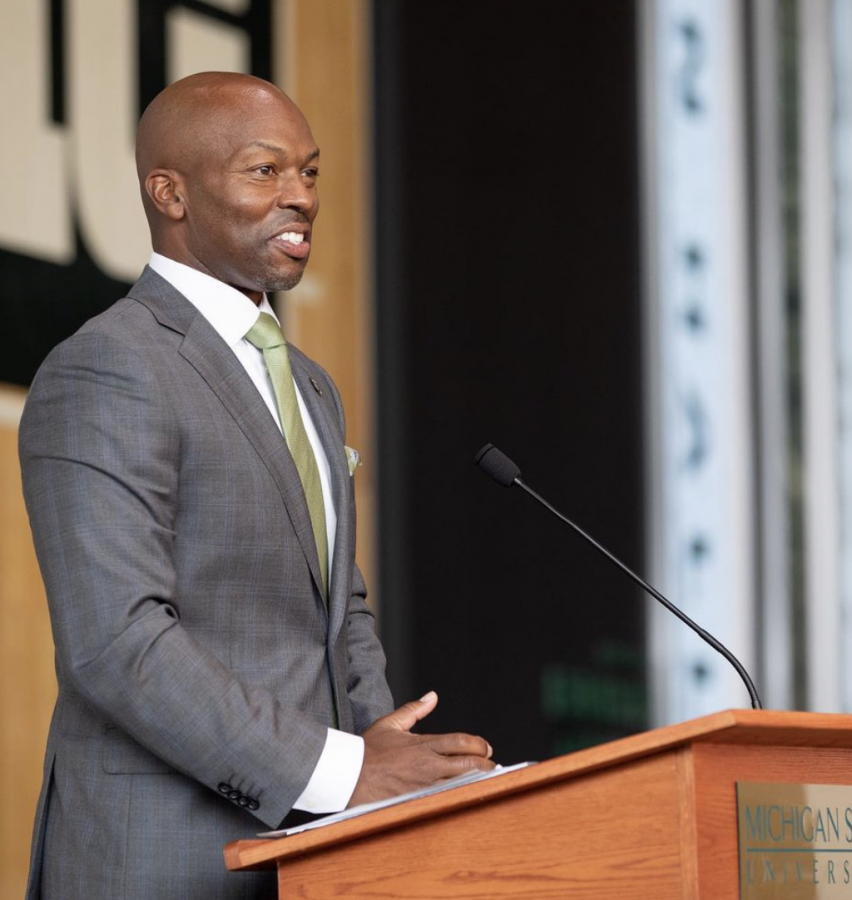

Joseph Kamaru, aka KMRU, was raised in Nairobi, Kenya, and currently studies Sound Studies and Sonic Arts at the Universität der Künste in Berlin. He has work dating back to 2017, but has gained notoriety only recently after releasing albums such as Peel and Jar in 2020. KMRU’s style of ambient is one that often banks on subtlety and gentle rhythms born of field recordings. As he said in an interview with Mezzanine, “Most of the time it’s investigative field recording, where I begin with an idea of a sound or place and explore single subjects in detail.” Using these clips of naturally-occuring noise, KMRU often leans into the drone subgenre of ambient, producing tracks both meditative and endlessly engaging in their repetitions. What has resulted is a quickly blooming catalog of some of the most beguiling sounds the genre has seen in recent years.

Noteworthy tracks by KMRU include “Why Are You Here,” “Life at Ouri” and “Well.”

“Why Are You Here” holds the soundscape of some empty field on some lonely night. As it loops and loops, it builds on itself, growing denser and louder before it reaches a peak of clear emotion where individual listeners may discover peace, numbness, melancholy or whatever else may have been waiting to be unlocked in them.

“Life at Ouri” is a bright piece that celebrates the wind and all the sounds it may carry. Distant voices are caught in it; quiet chimes and keys dance with them, fostering images of children playing in fresh grass under a kind sky. One word tells this track’s story: serenity.

“Well” is a track constant in its beauty and similar to “Why Are You Here” in its gentle drone. It is for 3 a.m. moon staring, for running a hand along cool midnight grass or for any frame of mind that simply needs peace. The mysterious power of “Well” truly represents all that KMRU is capable of.

Klein

Klein is a multi-genre singer-songwriter and producer from London, England. She’s released albums and EPs in the realms of R&B, electronic, industrial pop and more, often combining elements from multiple fields in each release. One of these fields happens to be ambient. Until she released the album Harmattan in 2021, she had only dropped flashes of ambient work, but her contributions can already be labeled as significant. Her refusal to be boxed in gives her a truly unique style, one almost free of comparison. Heavily manipulated audio samples and stilted drones make up much of what she creates. Further separating herself from the crowd, she cited Andrew Lloyd Webber and Soulja Boy as influences in an interview with Fact Magazine.

Noteworthy tracks by Klein include “Farewell Sorry,” “The Haunting of Grace” and “Not a Gangster but Still from Endz.”

“Farewell Sorry” is the outro to Klein’s 2017 EP Tommy. This track is incredibly lively and — even though Klein is almost free of comparison — is like a challenge to Oneohtrix Point Never’s 2011 album Replica. The boundaries of ambient are stretched nearly too far to fit within the known genre here: sporadic vocal samples and longing croons jump through the spiking, glitched instrumental base, leading to a soundscape that bends around the absurd. This track gives an outstanding case for why Klein’s work can be rightfully labeled experimental.

“The Haunting of Grace” conjures an atmosphere that can be seen as host to the death of a freighter lost at sea. From its ghastly foghorn, this freighter calls and calls and calls into nothingness. The track is slow and haunting — as the title would suggest — but then it merges into a beautiful rising shimmer about halfway through. Gold is practically laced into this rise; great beams of light accompany. It is decay then rebirth, the transition from hell to heaven.

“Not a Gangster but Still from Endz” is the shortest track on Harmattan at just over a minute, but it is certainly one of the project’s most interesting arrangements. It provides a dark, mysterious backing for an explosion similar to the foghorn of “The Haunting of Grace” and holds an intro and outro equally strange in their sudden sprintings. Its short time span increases its allure: it is easy to find oneself replaying the track over and over to investigate all that occurs within its frame. As with Klein’s whole artistic career, it is something unique and consistently mystifying: Understanding what is at the center is no small task.

Ibukun Sunday

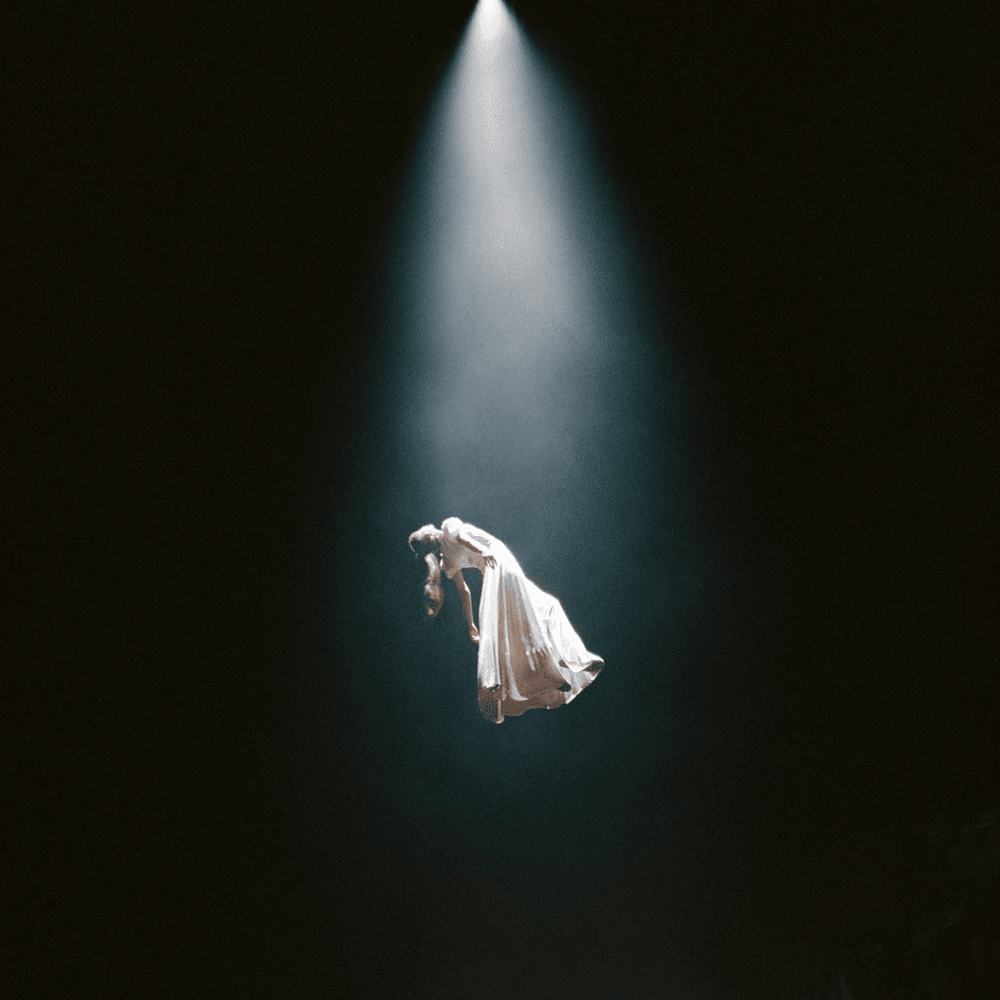

Nigerian violist and electronic musician Ibukun Sunday is relatively new to the ambient scene, having released his debut EP The Last Wave on Oct. 22, 2021, but the potency of his current output is that of an esteemed veteran. As written on his Bandcamp, what hangs over the EP is a “heavy, apocalyptic dread” which contrasts with occasional moments of respite. From the overarching soundscape’s mass of rolling dark clouds come passages lining the storm with an unexpected, cautionary warmth. He meshes these opposing forces by placing the heavy fuzz associated with ambient titans like Tim Hecker against melodies closely aligned with the West African music scene around him. Though Ibukun Sunday is fascinated with ambient’s ability to display the end times, he states that “my music gives me hope again” because in his field recordings and samplings of nature, there is peace. In his artistic pursuits, he finds contentment.

Noteworthy tracks by Ibukun Sunday include “Shadows (The Light of Light),” “No Turning Back” and “Saints And Sinners.”

“Shadows (The Light of Light)” is Ibukun Sunday’s first single, released on Nov. 25, 2020. It is not as concerned with the end times as tracks on The Last Wave, as it remains tame throughout. It sways back and forth as a flower would in gentle winds, calling for glistening plumes to rise from the muted stream making up the background. It seeks to answer the question “What does bliss sound like?” and is more than successful.

“No Turning Back” sounds hopeless, as if it would be played for a future city long-abandoned, long-buried, never to be uncovered. It is the antithesis of “Shadows (The Light of Light)” in all facets except that it is deeply engaging. It is harshly digital, harshly electronic, like it’s warning of an approaching doom at the hand of something artificial. As the track trails off, nothing is left but uncertainty.

“Saints And Sinners” is Ibukun Sunday’s longest track, sitting at 9 minutes, 24 seconds in runtime. It shares elements of both “Shadows (The Light of Light)” and “No Turning Back,” marrying peace and desolation, placing the listener on a plane devoid of everything but an unceasing apocalyptic wind. It is slow, yet thorough. Simple, yet strangely fascinating. From this base, Ibukun Sunday is sure to grow an enchanting discography.

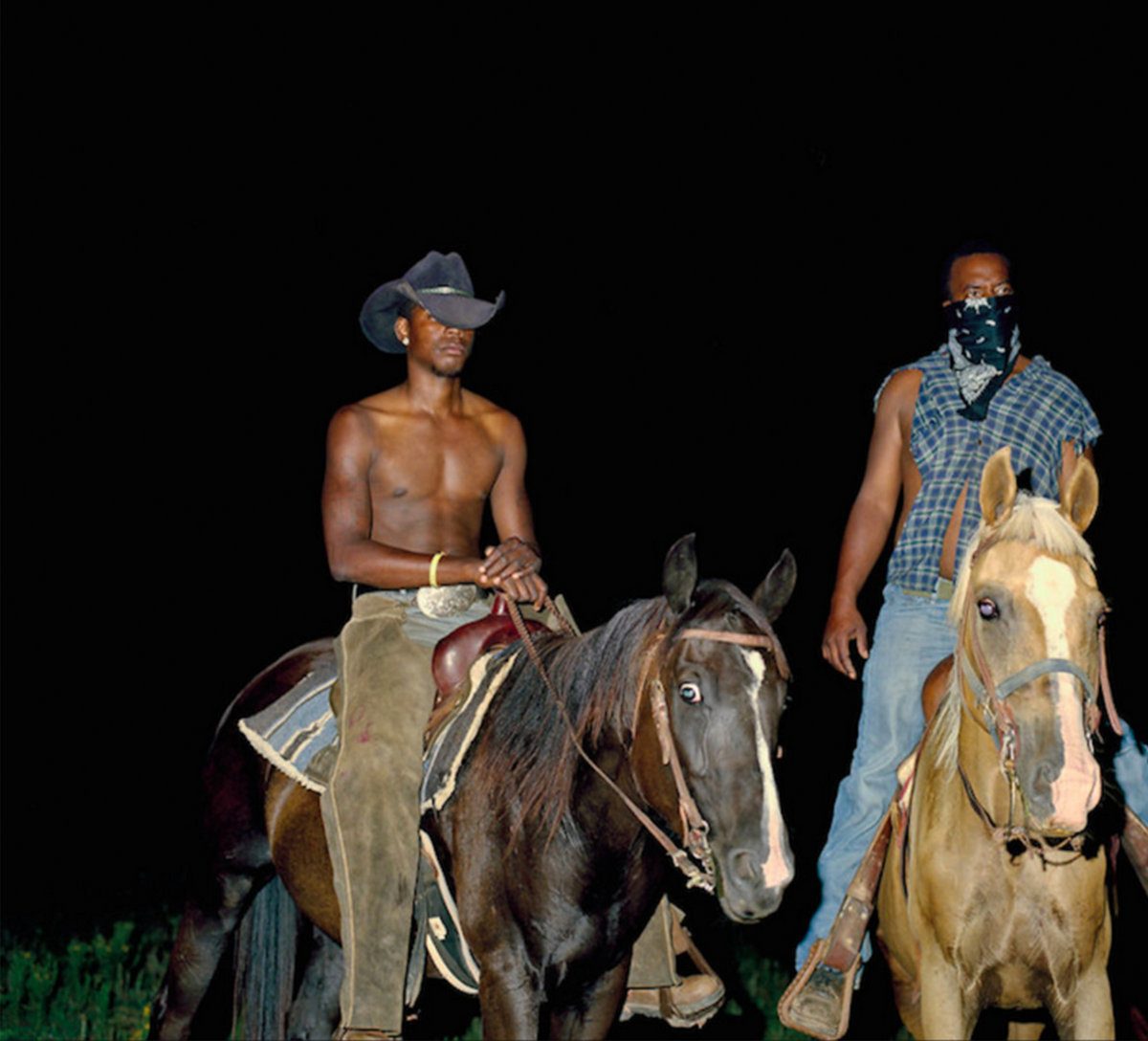

Dedekind Cut

Fred Warmsley, aka Dedekind Cut, is a California-based producer known for his work in the spheres of hip hop, breakcore, noise and ambient. He has collaborated with artists such as The Alchemist, Joey Bada$$ and Hieroglyphics in the past, primarily on hip hop projects, but his most recent output has typically been focused on ambient, drone and noise. Warmsley’s first release under the name Dedekind Cut was the now-unavailable tHot eNhançeR EP in 2015, and his first studio album, $uccessor (ded004), was released the following year. Following his output as Dedekind Cut, Warmsley released बड़ा शोक (heart break) under the name Barrio Sur in 2018 and has sparsely been involved in the world of music since. At the tail end of many name changes and genre-shifts, the work of Dedekind Cut is as intriguing as the man behind it. This is a body of work that can simply be labeled as beautiful: trying to word it any other way risks dishonesty.

Noteworthy tracks by Dedekind Cut include “Integra,” “Spiral” and “Das Expanded, Untitled Riff.”

“Integra” is a track transmitting a delicate, almost unrecognizable nostalgia to its listeners. It is a love letter to rain and memory, reaching out to anything calm. The sounds within are unmistakingly human, yet it feels like something that could only be made by someone watching from above. In mortal actions like staring at crashing waves, staring at star-filled nights or staring at nothing but the closed lids of one’s eyes, “Integra” resonates deeply, even though the track’s core elements can be so difficult to bring down to Earth.

“Spiral” pushes forth an atmosphere of controlled, chiming chaos. Bursting from darkness into a kaleidoscope of rushing light, it eventually latches onto sounds of nature. In this grand rush are the chirps of birds, the rustling of frogs, deer or any other creature of the forest, and the faint pattering of rain against leaves. From confusion eventually comes that euphoric glimpse of the clearest of images, as well as the most natural. How easy it is to become lost in the swarming beauty of this track.

“Das Expanded, Untitled Riff” finds its base in a repeating piano arrangement and grows steadily into angelic callings, walls of dark synths and passages of toned-down harsh noise washing over each other. These sounds belong to science fiction; similar to the working parts of “Integra,” it is hard to believe they are from this world. The fact that a soundscape like this is possible is truly incredible: toward the advent of the ambient genre, who was to expect this would eventually be a product?

Obviously, much has changed since ambient’s beginnings, and much more will change in the future. Just as Black artists like King Tubby and Laraaji left their mark on the genre, KMRU, Klein, Ibukun Sunday and Dedekind Cut have and will continue to leave theirs. In a genre that has typically been viewed as overwhelmingly white, these artists are making their voices heard and inspiring new voices to rise. The great canvas that is ambient has much more space to fill in the near future: Those spaces are certainly in good hands.