Beats Without Borders | Astrud Gilberto & Bossa Nova

February 12, 2020

When discussing the impact of music across cultures, we have to talk about bossa nova. Birthed from the young artists of Rio de Janeiro in the late 1950s, it combines American jazz with Brazilian samba. What makes it most notable is the full-circle delivery of bossa nova to the U.S. via hit singles like “The Girl From Ipanema.”

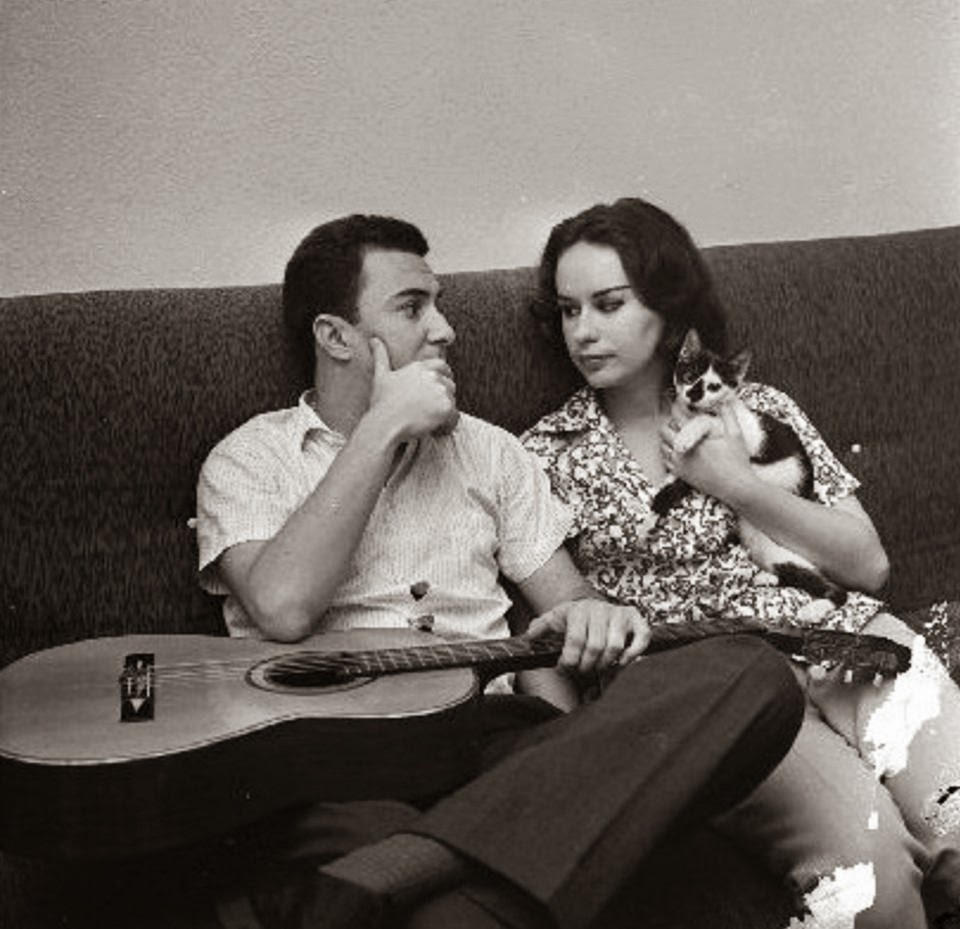

Antônio Carlos Jobim joined forces with Brazilian guitarist João Gilberto, both of whom are considered to be the fathers of bossa nova, and American jazz saxophonist Stan Getz to record this ground-breaking hit.

However, there’s someone outside this musical trio that made the song explode, and somehow we never talk about her. She’s not even the girl from Ipanema, but rather a young woman from Bahia: the mysterious singer of “The Girl from Ipanema,” Astrud Gilberto.

Astrud met João when she was just a teen as he led what she called their “musical clan,” which would later be given credit to the development of bossa nova. These middle class, college-aged students who lived in Rio wanted a music that reflected the simplicity and sensuality of the beach, despite the underlying political turmoil.

After emerging during a loosened government grip on the music industry, bossa nova quickly faded as people drew attention to the staggering regional inequality. People felt its frivolity ignored the struggle of those in poverty because it was detached from cultural traditions and values. However, when we analyze the bossa nova to its core, it reflects this juxtaposition almost perfectly. What is now commonly mistakenly referred to as “elevator music” has complex beginnings.

At the surface, songs like “The Girl from Ipanema” sound simple because the style is so “lazy” and unassuming; but beneath Astrud’s melty vocals, there is absolute precision to every part. João’s guitar-playing combines the harmonic twists and turns of jazz with the off-kilter rhythmic complexities of samba, and somehow makes it sound effortless. For instance, the chord change when she says “Oh, but I watch her so sadly” is an unexpected pang. However, through a few hairpin turns in the harmony, João gets us back to sonic home by the time Astrud sings “Tall and tan and young and lovely, the girl from Ipanema goes walking,” again. The musical moments that happen in bossa nova are small, but frequent and effective if you are listening for them.

So if the complexity lies in the instrumentation of bossa nova, why do we care about Astrud Gilberto? While bossa nova music showed how to make something complex sound simple, it was Astrud’s vocals that soaked the songs in sensuality. There was something so mystifying about her speak-singy voice falling over the bouncy songs. There was something cool and sexy about her nonchalance, and that’s because it had not really been done until that point.

In most popular forms of music, singers still incorporated the classical technique that had reigned since the beginning of opera in the 16th century. Huge voices with vibrato decorating ornate melodies showed true musicianship and vocalism. Astrud paved the way for many famous voices because it was no longer about learned skill, but rather someone’s one-of-a-kind, innate tone. There’s something so vulnerable about just singing naturally that listeners really connect to.

Through her carefree singing she uncovered a feminine sensuality and power that inspired so many women after her. Soon after bossa nova’s birth in the ‘60s it became written off, but there is value in its appreciation of life’s simplest pleasures. As recent popular music developed, the subject matter of sexuality and pleasure became much less taboo. Astrud and the other bossa nova artists, like Antônio and João, just played into one of the main functions of music: escape.

Astrud Gilberto sang lovely tunes of life’s beauty, so that people could leave their lives for a moment. She sang of going to tropical havens in songs like “Non-Stop To Brazil,” but beneath the physical imagery of planes and skies she is really talking about the human emotion of yearning. The power of her music lies in the songs like that, where she bares her soul so unassumingly.

In her neglected solo works like The Shadow of Your Smile, she sung of far more than sex and beaches; she speaks of her deep-laden fear of loneliness in “Who Can I Turn To.” Through simple yet unexpected melodies, like when she emerges into a new harmony the words “where destiny leads me.” In the biting “How Insensitive,” she introspectively discusses the painful reality of realizing you are no longer in love. She is further illustrating the simple complexity of bossa nova by singing of the highs, lows, and in-betweens of life through “simple” melodies.

Because of this, it’s easy to ignore the depth of her songs. For instance, upon first listening to “Photograph,” I thought it was a cute, little song. After looking up the translation, I saw that it was a melancholic story of being away from a lover. After knowing this, the music sounded different. Every little chord shift and melodic suspension hinted at this slight worry of heartache; her faded “oo’s” turned into soft cries. Everything is intentional. Every note and word and strum holds weight. It takes something special to make that sound so uncomplicated.

Astrud’s solo take on bossa nova is special because it took the artform a step further. She added honesty, vulnerability and the female lens to the gentle rigidity of bossa nova instrumentation. Her voice and stories directly reflected the music’s emotive nuances and femininity. She wasn’t the girl from Ipanema – she was far more.